Counting down the 25 most “significant,” meaning shows with lasting cultural implications, and/or “notorious” nights in Austin music history. Big outdoor festivals are excluded because they’re multi-act extravaganzas take place in parks, not clubs or auditoriums. I’ve also put SXSW into exclude mode because it’s got its own history and Austin isn’t really Austin in the middle of March.

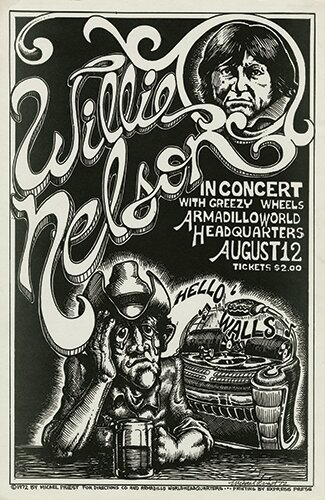

#1 Willie Nelson at the Armadillo August 12, 1972

This concert was the Big Bang of modern Austin Music, the show that begat the “progressive country” movement that put Austin on the map as the anti-Nashville. Willie Nelson had discovered, on previous trips to Austin, especially the musically-thrilling financial disaster that was the Dripping Springs Reunion in March 1972, that Texas hippies loved country music. After years of wearing a suit and short hair, trying to get the country mainstream to accept him, Willie said “screw it” and moved to where his true audience was.

One of the longhairs who loved his music was Armadillo World Headquarters ringleader Eddie Wilson, who wore out the grooves of Willie’s Live At Panther Hall album while homesick in the Bay Area for a month. When Wilson returned to Austin and the Armadillo and heard Willie, wife Connie and the kids had moved to nearby Riverside Drive, he made it his mission to book the straight-laced Nelson into his hippie beer joint. It wasn’t hard, as Willie stopped by the Armadillo soon after getting his utilities turned on. “I’ve been looking for you,” Eddie said. “Well, you found me,” answered Willie.

You have to realize that 1972 was still the Sixties in Austin, with the thick air of conflict whenever crewcutted rednecks and longhaired peaceniks were in the same establishment. It was jocks vs. nerds, bullies against the passive, with the war in Vietnam drawing a line that felt like a moat. But the debut of Willie and his band, with the wildly popular bluegrass stoners Greezy Wheels opening, brought both sides together without incident. As conducted by Willie, who had just started growing out his hair, two quite divergent groups of people realized, through the shared experience of music, that they had more in common than they had thought. A cliché brought to life on Aug. 12, 1965, when the Vulcan Gas Company merged with the Broken Spoke.

As the creator of songs (“Crazy,” “Hello Walls” etc.) that made a lot of people a lot of money, Willie came with heavy music business connections, which was something the Austin music scene needed badly, lest all this heartfelt music disappear at the end of the night. He bought a complex on Academy Drive near South Congress Avenue and opened Arlyn Studio- Austin’s first world class recording facility- and the Austin Opera House, which took over as the best place to see shows after the Armadillo closed on New Year’s Eve 1980.

After Willie’s successful debut at the Armadillo, he started getting his country rebel friends like Waylon Jennings to play there, and stoked a national fascination with “Waylon and Willie and the boys.” Austin earned an identity in the ‘70s as the capital of outlaw country music. Then came the Vaughan Brothers and Clifford Antone and the blues. Then came all the indie rock guitar bands.

There’s been amazing music in town since the German singing societies in the late 1800s. This is the town of the Lomax family, who saved folk songs like children in burning buildings, where Kenneth Threadgill gave a foul-mouthed free spirit named Janis Joplin a place to sing. The wealth of live music continues today, with nurturing venues like the Mohawk, Beerland, the Continental Club, Hole In the Wall and on and on keeping the legacy alive. Willie didn’t start great live music in Austin, but he became its spiritual leader. Like his close friend Coach Darrell Royal, Willie set a high standard. It’s OK if you can’t reach it, but not cool if you don’t even try.

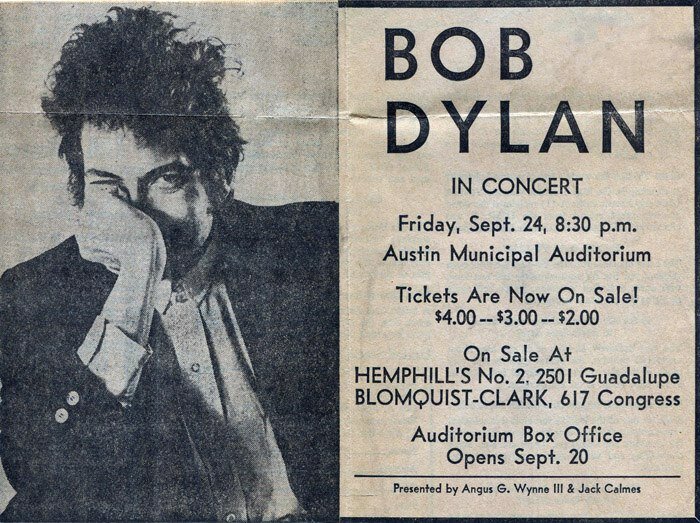

#2 Bob Dylan at Municipal Auditorium Sept. 24, 1965

The first time Bob Dylan was ever backed by Robbie Robertson, Rick Danko, Richard Manuel, Garth Hudson and Levon Helm in concert was in Austin in the fall of ’65. Dylan was 24 and had just released the controversial, unfolky masterpiece Highway 61 Revisited. The first set was Dylan acoustic- “Gates Of Eden,” “It’s All Over Now, Baby Blue,” “Desolation Row” and “Mr. Tambourine Man”- and then out came the five guys who would later be called the Band. It was The First Waltz.

The Austin show was only the fourth time Dylan had played electric, and the first time he hadn’t heard boos from folk purists who pegged him as a pop sellout trying to glom onto the Beatles phenomenon.

“It never entered my mind — or heart — not to love the electric stuff,” said NYC photographer Stephanie Chernikowski, a former Austinite who was at the show. “It was so in-your-face,” promoter Angus Wynne recalls of the Austin electric segment. “You couldn’t really understand the words — quality concert sound systems were nonexistent back then — but you could feel the energy. It was like being knocked over by this huge burst of sound.”

Dylan held a loose press conference at the Villa Capri motel, where he and the Band were staying, the afternoon of the First Waltz.

Wynne, a 21-year-old fledgling promoter, had decided to try to book Dylan in Austin and at Dallas’ Moody Coliseum the next night after repeatedly hearing “Like a Rolling Stone” on the radio after its July 20, 1965 release. “I looked at the back of a Dylan album and it said he was managed by Albert Grossman, so I called information in New York and got the number,” Wynne recalls. “When I called and made my pitch, someone yelled to the other room, ‘Hey, do you want to go play in Texas?’ and someone yelled back ‘Yeah, sure.'” That’s how things went back in the days before big-scale national tours.

Dylan had met the Band when they were the Hawks, the former backing band of Ronnie Hawkins, a year earlier. They were reacquainted in August 1965, according to Clinton Heylin’s “A Life In Stolen Moments: Day By Day 1941-1995,” when Grossman’s secretary took Dylan to see the Hawks at a club in New Jersey. He hired away guitarist Robertson and drummer Helm, an Arkansas native, to play somewhat coldly-received concerts in Forest Hills, N.Y., on Aug. 28 and the Hollywood Bowl Sept. 3. Bassist Harvey Brooks and keyboardist Al Kooper rounded out that band.

Dylan flew up to Toronto on Sept. 15, nine days before the Austin show, to rehearse with the Hawks. Three nights later he was back in New York. The Band was ready.

Although Helm quit the group two months later, due to an aversion to being booed night after night, Dylan and the rest of the Hawks forged on to Australia and Europe with a series of fill-in drummers before settling on Mickey Jones of Dallas. Then came Dylan’s motorcycle accident in July 1966, which, though not seriously injuring him, gave Dylan an excuse to lay low for a while.

During this period of mental healing, Dylan woodshedded daily with the Band, the informal sessions captured on an Ampex reel-to-reel tape machine. May to August 1967 was a summer of inspiration, as a relaxed Dylan started to get more of a feel for the Band’s earthy instincts. The oft-bootlegged sessions (officially released in 1975) were called The Basement Tapes.

After blaring a hundred frantic solos a night behind Dylan’s spitfire lyrics (and the gritty Southern roots of Ronnie Hawkins before that) the Band, off the road for the first time in years, fell into a more unforced approach to collective song making, and painted the masterpieces Music From Big Pink (1968) and The Band (1969).

When Dylan toured again, almost eight years after his 1966 world tour ended with the legendary concert at London’s Royal Albert Hall, his backing group was once again the Band. This time they weren’t anonymous sidemen but artistic peers.

When the Band played for the last time all together on Thanksgiving night 1976, Dylan joined them to perform “Baby Let Me Follow You Down,” which front row-seated Don Hyde, inspired to co-found the Vulcan Gas Company two years later, said opened the electric segment on Sept. 24, 1965.

It was a glorious and enriching collaboration, which began in Austin, Texas, and will be commemorated with a 50th anniversary tribute concert next September at the Long Center, where Municipal Auditorium once stood.

#3 Hank Williams at the Skyline Club Dec. 19, 1952

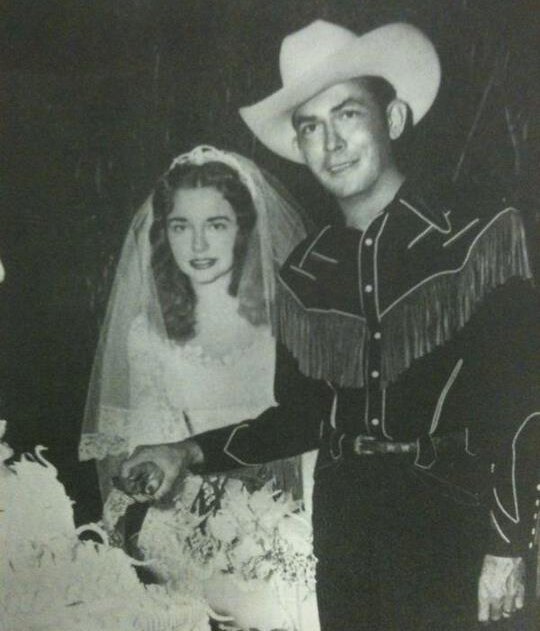

Billie Jean and Hank Williams October 1952.

Skyline Club owner Warren Stark drove Hank Williams from Dallas, where he’d played on Wednesday Dec. 17, because that was the only way to ensure that the greatest country songwriter of all time would show up for the gig. “Mr. Lovesick Blues” was in a bad way with drink and drugs, traveling with his own phony doctor a la Elvis Presley to stay medicated on a roller coaster of ups and downs. But the Friday night show at the Skyline, which turned out to be the legend’s final public performance, was one of his best of the tour according to brother-sister opening acts Tommy and Goldie Hill of San Antonio. Backed by the house band, Hank played two sets and, according to Chet Flippo’s essential biography, threw in a few gospel songs, which was rare for Hank at a honky tonk.

Former Austin singer Jerry Green, who went on to be a regular on the Louisiana Hayride, spent the day of Dec. 19 with Williams. “Justin Tubb (Ernest’s son) was going to UT at the time and I was friends with him and the Tubb Boys, so we spent the day with Hank Williams,” Green told me in 2011. They all visited the Hays Record Shop (916 E. First St.) and then Green dropped Williams off at the Stephen F. Austin Hotel. “Hank was trembling something fierce that day,” said Green, “but when he played, he did a fine job.” No doubt a little help from Dr. Toby.

Williams had married the former Billie Jean Eshlimar, a 19-year-old divorcee from Bossier City, LA, just two and a half months earlier, at two ceremonies- one for family and one for anyone who’d bought a ticket. She accompanied him to a private party for the musicians union in Montgomery, AL, Hank’s hometown, on Dec. 28, 1952, when Williams got up from his steak dinner to sing a few songs on an acoustic guitar. But the Skyline, way outta town on the section of far North Lamar called the Dallas Highway, hosted his last concert.

Hank Williams died of a hemorrhage of the heart, brought on by drug and alcohol abuse, 12 days after the Skyline show. His body was discovered without breath in Oak Hill, WV, when his driver came out of the Skyline Drive-In (!!!) with coffee for the drive to a gig in Ohio. Billy Jean performed for about a year as “Mrs. Hank Williams,” but then met and married an up-and-coming Johnny Horton in September 1953, and let him do all the performing. Horton had his first hit three years later with “Honky Tonk Man,” though he was best known for history-based songs such as “North To Alaska” and “The Battle of New Orleans,” both #1 smashes.

In an eerie coincidence, Johnny Horton’s last show was also at the Skyline. After playing a show there on Nov. 4, 1960, Horton was killed driving home to Shreveport by a drunk driver in Milano, TX. You can be sure Billie Jean’s next husband wouldn’t go within 10 miles of the Skyline, which was built in 1946 and torn down in 1989 to make way for the expansion of Braker Lane. Everyone from Elvis Presley (1955) and Scratch Acid, who played their very first show there, had graced the Skyline stage. During the early ’80s it served as the second location of Soap Creek. A CVS drug store now stands at the former Skyline location at North Lamar and Braker Lane.

#4 Louis Armstrong at the Driskill Oct. 12, 1931

Louis Armstrong 1935, courtesy Universal.

This list has mainly been about what’s happened onstage, but this entry makes the top five because of what was going on with someone in the audience. Charles L. Black Jr. was a white Austin teenager, a freshman at the University of Texas attracted to Sixth Street for the possibility of meeting those of the opposite sex. He saw a placard advertising “Louis Armstrong, King of the Trumpet, and His Orchestra” for 75 cents admission and, though he had never heard of Armstrong at the time, he bought a ticket.

That jazz concert was the pivotal moment in the life of a local kid who became a noted Civil Rights attorney and taught constitutional law at Columbia and then Yale for almost 50 years. Black helped Thurgood Marshall draft the brief for the 1954 Supreme Court victory in the case known as Brown vs. Board of Education, a decision which declared school segregation unlawful and galvanized the movement to end the racist white regime in the South.

“It is impossible to overstate the significance of a sixteen-year-old Southern boy’s seeing genius, for the first time, in a black,” he wrote in a 1979 essay “My World With Louis Armstrong” which was published in the Yale Review. Documentary filmmaker Ken Burns quoted Black’s piece, which you can read here, in the lengthy segment of the 10-hour documentary Jazz about Louis Armstrong, the greatest musician America has ever produced. “We literally never saw a black man, then, in any but a servant’s capacity,” Black wrote.

The fall of 1931 was an interesting juncture in Armstrong’s career. He had lived in California briefly, but was exiled by a pot bust. Meanwhile, his manager Johnny Collins was mixed up with the mob, so Chicago and New York were too “hot,” which sent Satchmo out on tour in the Midwest and South with his new orchestra, led by arranger/trumpeter Zilner Randolph. Armstrong had just turned 30 and had already given birth to swing with adventurous Hot Five and Hot Seven combos that helped popularize the Lindy Hop. His singing on such numbers as “Ain’t Misbehaving” and “Heebie Jeebies” invented a phrasing style that defines jazz vocals to this day.

Just three weeks after his Driskill gigs, Armstrong and his orchestra stepped into a Chicago studio and changed jazz forever again. Recasting Hoagy Carmichael’s “Stardust” and “Georgia On My Mind” as jazz expressions, the American Songbook became a favorite platform for improvisation. With his frequent flights of innovation, no musician better deserves to have an airport named after him than Louis Armstrong in his native New Orleans. “Pops” returned to play in his hometown for the first time in nine years in 1931, the week after the Driskill stint, but was disgusted by the racism he encountered daily.

Charles L. Black would help write legislation to sweep away such Jim Crow nonsense and we have to wonder where would his studies have pointed him if not for that night of Oct. 12, 1931. The hold of Armstrong never left him. “All through those years, he was letting flow, from that inner space of music, things that had never before existed,” wrote Black, who died in 2001 at age 86. When they say the Driskill Hotel is haunted, they’re right.

SIDEBAR: Not significant, just notorious.

#5 Muddy Waters with Johnny Winter opening at the Vulcan Gas Company August 2 & 3, 1968

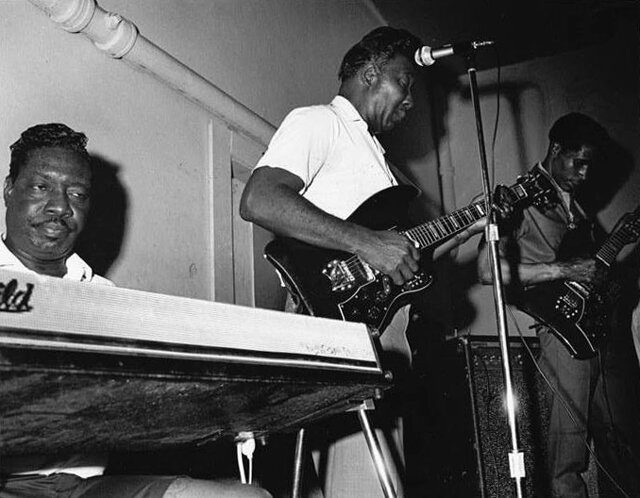

James Cotton, Johnny Winter, Muddy Waters 1977

Electrifying Beaumont guitarist Johnny Winter was instrumental in exposing the legendary Chicago bluesman Muddy Waters to ‘70s rock audiences, producing and playing guitar on the 1977 comeback album Hard Again and its crossover gem “The Blues Had a Baby and They Named It Rock and Roll.” But the duo had never met before playing on a bill together- Winter’s trio opening- at the Vulcan Gas Company in the summer of ’68.

On the first night, a Friday, the Waters band didn’t arrive at the Congress Avenue club until after Winter finished. “They did a standard 45-minute set,” Vulcan co-owner Don Hyde recalls. The band wasn’t even wearing their customary suits, as photos by Burton Wilson show, with piano player Otis Spann’s glare at the camera underlining the mood of the set. “It was only 10:45 (when they were done), so I asked Johnny if he would play for a couple hours more and he said sure.”

Muddy was still in his dressing room when Winter came back out and blew the doors off the place. The blues great came out to the side of the stage and his jaw dropped at the albino’s authentic blues style. He found a pay phone backstage and put in a collect call to a friend in Memphis. Hyde was standing next to Muddy when he held up the phone for about a minute during Winter’s set and then returned to the receiver. “He white!” Waters exclaimed. “I mean, he REALLY white! Can you believe this shit?”

The next night, the Waters band showed up in sharp suits and played a magnificent two-hour set that left no question about who was the master and who was the protégé. Muddy called Johnny up for a couple songs and a bond built of mutual respect was born.

Muddy’s harmonica player at the time, Paul Oscher, now lives in Austin and plays C-Boy’s every Thursday evening. “I think maybe we’d been driving all day Friday and we were tired,” he said, when asked about the quite-different sets the band played. “And then we were well-rested on Saturday and got down to business.” According to Waters itinerary records, the band drove all the way from Chicago to play the Vulcan.

First night: Otis Spann, Muddy Waters and Georgia Boy Snake at the Vulcan August 2, 1968. Photo by Burton Wilson.

Two weeks after the gig with Muddy, Johnny and his rhythm section of bassist Tommy Shannon and drummer Uncle John Turner recorded their first album The Progressive Blues Experiment live at the Vulcan during the day, without an audience. The LP, originally released on Austin’s Sonobeat label, then sold to Imperial, contains the Winter’s original “Tribute To Muddy.”

After the Vulcan closed in the summer of ’70, Muddy moved over to the Armadillo for Austin shows, but found a new home in 1975 when Clifford Antone opened his first club on Sixth Street, across from the Driskill Hotel. Waters and his band played Antone’s five straight nights, starting Oct. 21, 1975, and in the audience each night were Stevie Ray Vaughan, members of the Fabulous Thunderbirds, Lou Ann Barton and others who would define the Austin blues scene for decades to come. The essential Chicago bluesman, Muddy Waters died of heart failure in 1983 at age 70. Johnny Winter also lived to be 70, dying this past July while on tour in Switzerland.

#6 Gloriathon at Liberty Lunch July 23-24, 1999

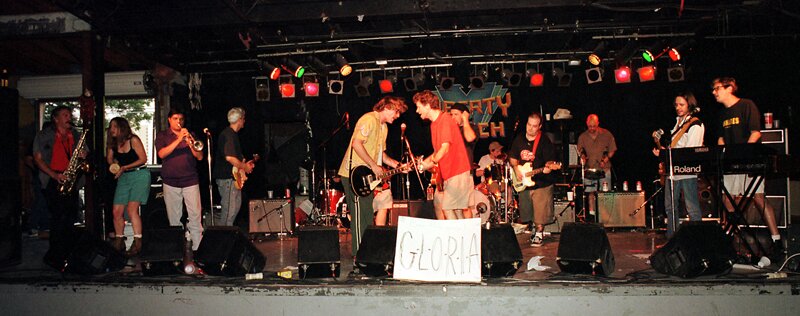

Photo by Kevin Virobik-Adams

Many would choose to list the 1974 Van Morrison concert at the Armadillo World Headquarters where he played seven encores. But I picked the show where he just phoned it in.

Liberty Lunch was the Armadillo in the trousers of ‘80s and ‘90s Austin. It was a special, no-frills club where all the greats played on their way up, where the folks who ran the place were happy if you were. The club was on city property, paying $600 a month rent on a plot worth millions, so its demise was eminent. When the singer of Afghan Whigs was hospitalized with a fractured skull after a fight with a stagehand it seemed to validate the heave ho, and the Lunch had its date with the ‘dozers. It was the end of July ’99 and Texas Monthly writer Michael Hall put together a send-off of epic proportions. He and anyone else who wanted to would play the Van Morrison garage rock anthem “Gloria” for 24 hours straight.

Hall’s short-lived band the Brooders started the one-song marathon at 9 p.m. Friday July 23, kicking it off in a trance of vibrato guitars for 15 minutes. And then Hall started singing those lines that launched 10,000 bands; “She comes ‘round here…” It was another 45 minutes until the chorus was reached like a climax. “G-L-O-R-I-A, Gloria!” Twenty-three more hours to go.

The concept was brilliant- 1952 Greenwich Village brilliant- but how could Hall and company possibly keep it up? Who’s going to play at 5 a.m.? Or two in the afternoon? But the Austin music scene showed up. All night, all day. Jam bands, blues players, shuffle drummers and sax players. One musician came offstage at 4 a.m. to find his car missing, so he went down to the station, filed a report and went back to the club in the morning light, played another hour- and then found his car exactly where he’d parked it the day before. One drummer was so wasted he just pissed up against the back wall of the stage. Fresh beers were distributed at 7 a.m., like cups of water from strangers on the side of the road, urging on the marathoners. It was just craziness, but the sense of community fueled the whole thing. Customers became musicians- playing on the stage that once held Nirvana, Bill Monroe, My Bloody Valentine, the Neville Brothers, Foo Fighters, Wilco and on and on and on.

Every musician brought their own thing to the simple E-D-A chords that relentlessly built to a climax and then walked back down that hill to start over again. G-L-O-R-I-A, Gloria! That part never got old. The Gloriathon was a 24-hour orgy with bodies coming in and out all day and night. “Jesus died for somebody’s sins but not mine,” Gretchen Phillips sang it, Patti Smith style. This was our lives they were playing about.

At about three in the afternoon, Van Morrison’s road manager held up a phone as Van the Man sang “Gloria” at a festival in Scotland, and it was piped over the sound system at the Lunch. He didn’t normally perform the 1965 song anymore, Morrison said, but there were a crazy bunch of folks in Austin playing “Gloria” for 24 hours straight, so he dedicated it to them.

A great moment, for sure, but the superstar cameo was a deviation of what was really happening. We were not just toasting a beloved venue and the people who made it shine. We were saying goodbye to a paradise of our youth, a time and place that made us feel as if we finally belonged. The summer of ’99 marked the end of the ‘80s in Austin. It was time to start families, to get on with the work that would define us, to see what we were really made of, now that the fantasy was being torn down.

The last hour of the Gloriathon, with the finish line in sight, was the best. At 8 p.m., the crowd waiting outside to see Saturday’s headliner Joe Ely was let in, just as the stage was wailing, with about 20 people up there. Joe King Carrasco’s dog yelped into the same microphone as his owner- an insane harmony that felt right. The newcomers urged on the hodgepodge orchestra, and for awhile there was no song, just players. It was challenging, abrasive, yet full of purpose, and the audience pumped their fists at the ugly and beautiful dissonance. But here she comes. When they hit the final familiar chorus, something beautiful burst. The whole place, now jam-packed, was singing along and stomping. There is no sadness in the final climax.

#7 The Rolling Stones at Zilker Park October 2006

This was really a concert for the whole city, not just the 42,000 who had paid $95- $350 to be a part of history, the first time “the world’s greatest rock and roll band” played “the live music capital of the world.” Midway through the two-hour headlining set (Los Lonely Boys and Ian McLagan opened), Mick Jagger announced that they’d be doing a song they’d never played live before, then the band went into “Bob Wills Is Still the King” by Waylon Jennings. “No matter what goes down in Austin, Bob Wills is still the king,” Jagger sang, a nod to Texas music history that’s even bigger than the Rolling MF Stones!

With $4 million in ticket sales, the show was Austin’s highest-grossing single-day musical event ever, but the concert’s significance went beyond box office or that it was a truly rejuvenating, 21-song extravaganza. Fans glowed as if they knew they were part of something bigger than the live DVD being filmed that night. There was such an air of mutual respect between band and city, exemplified by the t-shirt merging the Texas Longhorns logo and the Stones’ tongue that sold out during the excruciating 90-minute lull between Los Lonely Boys and the main attraction.

I had a 10 p.m. deadline on a 25” scene-setter, so I left the show about an hour early and walked home to write. Outside the venue’s temp fence, Barton Springs Rd. was packed with hundreds of people who didn’t love the Stones $95 worth, but wanted to be able to tell their grandchildren that they’d “seen” them do “Satisfaction” live. (The 2,000 square feet video screens peeked through the trees.) On my deck, as I was filing, I heard “Sympathy For the Devil” as clear and relentless as if it was playing on my stereo. But it was the Stones in the flesh! Folks from as far away as Ben White Boulevard and Loop 360 could hear the concert from their porches, but only the assholes dialed 311.

When the various neighborhood associations surrounding Zilker Park signed off on ACL Fest as an annual event, they were assured that it would be the only fenced-in concert there all year. But Austin is just not a city that could say no to the Rolling Stones, and Zilker became the only park on the itinerary of the “Bigger Bang Tour” of football stadiums. Things have changed dramatically in the city with the violet, hey-what-the-hell-happened-to-the, crown. But we’ve got a statue of a blues player that folks come from all over the world to see. And we know that you do whatever it takes to host a concert by the Rolling Stones.

Although it was, by all accounts, a fabulous, once-in-a-lifetime concert by Paul McCartney at the Erwin Center last year, that show doesn’t make this list because a) Although his concerts are as close as we’ll ever get these days, McCartney is not the Beatles and b) it was at the Erwin Center, not Zilker Park.

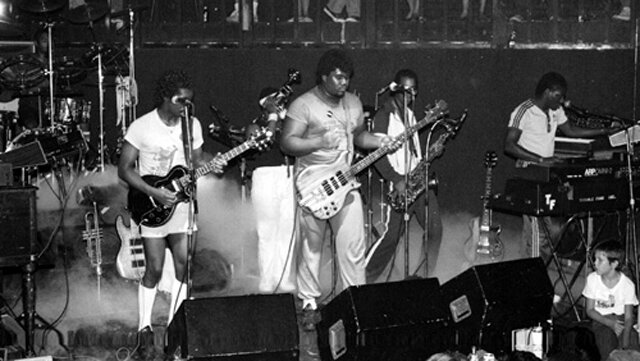

#8 Trouble Funk, Big Boys at Nightlife August 1983

Trouble Funk at Club Foot, er, rather Nightlife.

A year before the Red Hot Chili Peppers released their first album, punk rock and funk rhythm gloriously collided in Austin when the Big Boys, thrashers who had added a horn section, opened for Washington D.C. “go-go” powerhouse Trouble Funk at the Club Foot location at 4th and Brazos which had just changed names to Nightlife.

Although the genres sounded nothing alike, go-go and punk came from the same mindset of jumping off the pedestal and onto the dancefloor/moshpit. Both are people’s music. In an era when top R&B acts like the Commodores and Earth, Wind and Fire dressed like pimp spacemen, the members of Trouble Funk wore cut-offs and tank tops, “dropping the bomb” on pompousness in order to connect deeper. Using “call and response” from the church, TF roamed the soundscape in search of the original groove and once they found it, they didn’t let go. Repetition became hypnotic, with no breaks between songs. The most self-conscious people during the Trouble Funk set at Nightlife were the handful not dancing.

This monumental night came about because a critic for the Village Voice called the Big Boys a cross between ZZ Top and Trouble Funk. Roland Swenson, now director of SXSW, then the co-owner of Moment Productions, had a booth at New Music Seminar in NYC and met the members of Trouble Funk. Swenson showed them the Voice review and said that they should play a show with the Big Boys (a Moment client) in Austin. A couple months later, the “Don’t Touch That Stereo” tour was routed right through Texas. A call to Club Foot/ Nightlife brought the opinion that such a double bill was insane. “Club Foot said ‘You don’t understand. That band is a hardcore band and their crowd is NOT your crowd,” recalls Tim Kerr of the Big Boys. But Trouble Funk stood their ground. The club called the Big Boys, who said they were fans and could see the bill working, so the show was booked. The Big Boys had been turned onto D.C. go-go, which never really caught on nationally, by Ian MacKaye of Minor Threat, who stayed at Kerr’s house whenever he came through on tour.

Opening for Trouble Funk, the Big Boys brought the horns out more than usual and debuted their raucous version of marching band fave “The Horse,” which brilliantly set up Trouble Funk’s seamless feet-jack. “There were definitely people there to see Trouble Funk, not us, but the crowd was more than half Big Boys fans and Club Foot regulars,” Kerr says. After the show, members of the two divergent bands toasted the triumph.

“We told them there was a great scene in their hometown that loved go-go and when Trouble Funk got back to DC, they should get a hold of Ian at Dischord and do a show together.” The next month, Trouble Funk played a sold-out concert with Minor Threat, and the Big Boys, who instigated the whole thing, were brought in to open.

“It was a pretty big deal because it was the first time they had ever mixed the mostly white DC hardcore scene with the mostly black DC go-go scene,” Kerr says. “We were pretty honored to be asked, and it also turned out to be Minor Threat’s last show.” Folks in D.C. still talk about that historic night. But the pioneer performance happened in Austin a month earlier.

#9 Thanksgiving jam at the Armadillo World Headquarters Nov. 23, 1972

Photo by Burton Wilson.

The Grateful Dead had a gig at Palmer Auditorium the night before Thanksgiving and they worked up a deal with the nearby Armadillo to cater the pre-show meal for band and crew. As Jerry Garcia looked around the 1,500-capacity hall, which had re-opened after months of renovations just six weeks earlier, he said, “I’d love to play this place.” In earshot was owner Eddie Wilson, who said to tell him when. “Well, we’re not doing anything tomorrow,” said Garcia. The Dead had a day off, but only Garcia and bassist Phil Lesh were gonna be in Austin, as the rest of the band was headed to Corpus after the show with Frances Carr, who owned Manor Downs. Garcia’s good friend Doug Sahm said, “let’s have a jam session, man, and let everyone in for free!” Later that night, Leon Russell was backstage at the Grateful Dead show when Garcia asked if he wanted to stop by the ‘Dillo and play some piano. It would be an “Orphans Thanksgiving” to beat ‘em all.

The next morning, Eddie Wilson called up radio station KRMH (“Good Karma Radio”) and said that the ‘Dillo, which was scheduled to be closed on Thanksgiving, would be open after all for a free show. “A bunch of friends got nowhere else to go today, so they’re gonna be jamming,” Wilson said. Since the Dead had played the night before, it didn’t take most folks long to figure out they’d be involved. The special surprise was Leon Russell, who had the number two album in the country in ‘72 with Carney. Wilson was tight-lipped about his appearance because they didn’t want a bunch of people showing up and yelling out requests for “Tight Rope.”

Garcia, Lesh and Russell got there early, at about 3 p.m., but wouldn’t start until Sahm arrived about half an hour later. “Doug knows a thousand songs,” Jerry told Leon, who admitted later to Wilson that he was not much of a jam guy so “it was one of the worst days of my musical life.” Leon was on hand a month earlier when the Armadillo re-opened with a Freddie King show, after renovations doubled capacity from 750 to 1,500 and moved the stage from the south end of the building to the north end. “Freddie always called the Armadillo ‘The House That Freddie Built’ because that reopening show really got things going for us,” says Wilson.

Soon after the jam started, a torrential downpour bore down, so one of the first songs they played was “Stormy Monday” by T-Bone Walker. “It was my first realization of what a leader- an instigator- Doug Sahm was,” says Lissa Hattersley of Greezy Wheels. “They all played great, of course, but Doug was clearly the band leader of the night.” Garcia played pedal steel all night, with Sweet May Egan from Greezy Wheels a standout on fiddle on the first set, which concentrated on country songs, while the second set was more blues and rock. Russell played both guitar and piano and several local drummers sat in, including Jerry Barnett of Shiva’s Head Band. Hank Alrich, who would co-own the venue late in its run, had loaned his Stratocaster to various jammers and during a lull a cohort said, “Why don’t you go up and play your guitar? Everybody else has.” Alrich recalled his first number onstage: “As Leon kicked in to ‘A Hard Rain’s a Gonna Fall,’ rain began to fall on that old, big metal roof. This was before we’d gotten the underside insulated with spray-on paper foam, and the sound of the rain was the perfect touch to the intro.”

Twas a magical day and night, ending with an all-hands-on-deck medley of Chuck Berry’s “Roll Over Beethoven and Little Richard’s “Good Golly Miss Molly.” About 1,000 lucky fans had reason to be thankful that night.

Here’s the Nov. 23, 1972 music available for download here.

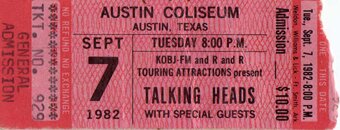

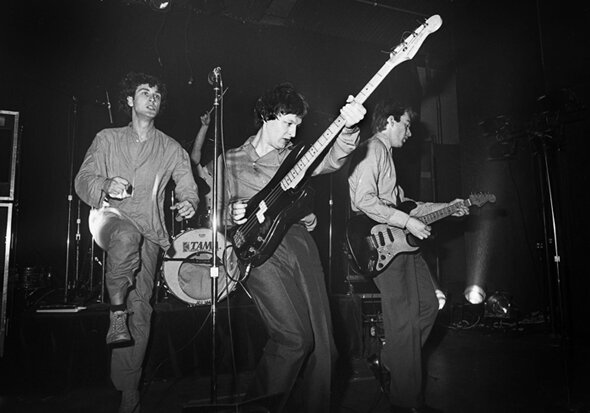

#10 Talking Heads at Fiesta Gardens Sept. 7, 1982

This was the NYC band’s 7th concert in Austin in four years and the first not at the Armadillo World Headquarters. Yet, although there were some amazing shows on Barton Springs Road, this was the T. Heads’ most notorious night in River City. First, the show was moved from City Coliseum with just a couple days notice when it was determined that, after a string of smoke-filled halls earlier in the tour, an outdoors venue would be healthier for eight-month-pregnant bassist Tina Weymouth. The neighborhood wasn’t sufficiently notified- or it didn’t matter if they were- so after the hip cutting-edgers invaded the Eastside enmasse on a Tuesday evening, some of their cars were negatively altered. One woman posting about this show on songwriter Edith Frost’s website recalled walking down a row of cars with their windows smashed out. But the show, sandwiched between Remain In Light (1980) and Speaking In Tongues (1983) was worth suffering mere property damage according to fan Rick Belden. “I was so euphoric by the time it was over that I didn’t even care that someone had spray-painted a black line down the side of my car during the show,” he posted. He kept it there to remind him of that fabulous night of heady dance music, ending with encores of “Take Me To the River” and “Cross-Eyed and Painless.”

Don’t know if the venue change ended up being such a great thing for Weymouth, who traded smoke for 100 degree heat, with her bass strapped on for two hours. But fan Lisa Wyatt Roe, who danced all set with 3,000 other ticketholders (plus those who exploited a breech in perimeter security by arriving by boat) said Weymouth was an inspiration. “She played so well, considering she was pregnant and it was a million degrees.”

Don’t know if the venue change ended up being such a great thing for Weymouth, who traded smoke for 100 degree heat, with her bass strapped on for two hours. But fan Lisa Wyatt Roe, who danced all set with 3,000 other ticketholders (plus those who exploited a breech in perimeter security by arriving by boat) said Weymouth was an inspiration. “She played so well, considering she was pregnant and it was a million degrees.”

The other Talking Heads show to consider was Nov. 21, 1980 at the Armadillo. This was a month after the release of the masterpiece Remain In Light, with its Afrobeat grooves, and the band was augmented by Adrian Bellew on guitar, Bernie Worrell on keyboards, and others. Every punk/new wave band in town wanted to open the show, but manager Gary Kurfirst gave the plum to legendary rock critic Lester Bangs, who had been using our fair city as a moveable flophouse for several months. Bangs had been rehearsing with various Austin players, but replaced them for the Armadillo gig with an existing punk band called the Delinquents. While the ‘Dillo crowd was known for acceptance and leniency, they booed Lester’s awful performance- at least the ones who were there. The hall didn’t start to fill up until just before the Heads set because Nov. 21, 1980 was when the world locked into its TV sets to find out “Who Shot J.R.?” on Dallas.

#11 The Huns at Raul’s September 19, 1978

Phil Tolstead gets hauled away. Photo from the Daily Texan.

Perhaps the most influential concert in Austin music history happened in San Antonio. Just a month after the Sex Pistols played Randy’s Rodeo in the first week of 1978, Austin’s first punk bands, the Violators and the Skunks, convinced the owner of a Tejano dive at the end of the Drag to let them have a night. And, thus, the Raul’s scene was born. Suddenly there were all these bands: the Dicks, Terminal Mind, Big Boys, Standing Waves, Re*Cords, Sharon Tate’s Baby, the Jitters, D-Day, the Next and on and on. Anybody could be in a punk band. That was the point.

On Sept. 19, 1978, a group of RTF students, lead by flamboyant singer Phil Tolstead, debuted their band the Huns at Raul’s with great anticipation. “The stage was set for theater,” Louis Black recalled in the Austin Chronicle nearly 30 years later. The Huns certainly weren’t going to wow people with their musical ability. “We sounded like the Sex Pistols with Sid on every instrument,” Huns drummer Tom Huckabee wrote in the liner notes of a 1995 reissue of The Huns Live at the Palladium 1979.

Inner Sanctum manager Richard Dorsett threw a trash can onstage to start the chaos that became the riot of 9/19/79. It was getting crazy, with band and audience both part of the show, when beat cop Steve Bridgewater sauntered in, just to check out what was going on. Tolstead spotted him and started directing the lyrics of “Eat Death Scum” at the man in blue: “I hate you! I hate you! I hate you!” Tolstead pointed at the cop and the cop pointed back. Some naughty words were said and the officer took the stage to arrest the singer for obscenity. And then he kissed him: Tolstead full on the lips of the cop, as he was being handcuffed. When officer Bridgewater put in a frantic officer-in-distress call, his radio was knocked out of his hand by the Huns guitarist and a melee ensued. But within minutes there were 10 police cars outside. There had also been a couple of plainclothes cops in the audience, according to a report in the Daily Texan, and when they started shoving people, someone poured a pitcher of beer over an undercover cop’s head and all hell broke loose. SXSW co-founder Nick Barbaro said “Are you proud of yourself, asshole?” to one cop, and he was arrested. Dorsett was also singled out as an instigator and he shared a cell with Barbaro that night. In all, six Raul’s patrons spent the night in the slammer, but then were released without charges.

Tolstead went to trial and was fined $53.50, but “The Huns Bust” has become such a exaggerated part of Austin clubbie lore that the six arrested grew into the “Huns 11” and 120 people on hand have multiplied to thousands through the years. But that night put Austin on the map as a place where other types of music besides “progressive country” was played. It also established the town as a place that doesn’t take itself too seriously. “I saw a cop walk onstage and I couldn’t believe it,” Huckabee said in the Daily Texan article on the incident. “We said on posters, ‘No Police.'”

The Daily Texan article was picked up all over the country and led to stories in Rolling Stone and NME. Riots at punk shows were big news. One of those who read the Rolling Stone story was a high school kid named David Yow, who joined the growing number of Raul’s regulars after the bust. “It changed the way I thought about music,” Yow has said. There was something going on with rock and roll and lines were being drawn. Many stepped over to the Raul’s side 36 years ago and never came back. Or they went the other way.

Tolstead became a born again Christian, a soldier in Jerry Falwell’s religious right crusade, in the mid-‘80s and appeared on The 700 Club, denouncing his past as a punk rock provocateur. That’s the strangest part of the whole story.

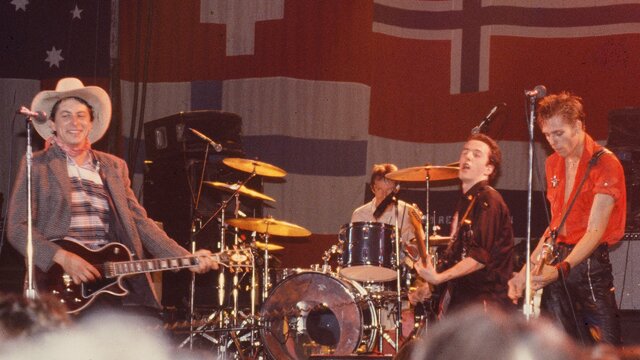

#12 The Clash with Joe Ely Band at the Armadillo Oct. 4, 1979

Photo by Mark Ely.

Someone described this show as Ely and his band pouring gasoline all over the stage and then the Clash coming out and lighting a match. “There was such an explosive feeling in the air,” says Ely. “I felt it. The Clash felt it. They had been disappointed with some of their first shows in the States, because some of the crowds were hostile and confrontational.” At one show fans cut the power cords with pocket knives, which makes no sense at all, and it was customary for fans to spit on punk acts from the U.K. But the ‘Dillo crowd was ready for a great rock and roll show and the Clash, Ely and opening band the Skunks gave it to them. Then everyone crammed into the Continental Club and jammed all night.

Three years later the Clash, in town making the video for “Rock the Casbah,” would play two nights at City Coliseum, where their opening act Stevie Ray Vaughan was booed the first night and replaced the next. But Ely’s set wasn’t met with such wrath from diehard punks because the Clash made it clear they were fans. “Our attitude was ‘it’s Saturday night at the honky tonk and someone just shot a gun into the ceiling,” Ely says of the Armadillo show. “It was one of those dangerous night where anything can happen.”

The modern singing cowboys from Lubbock met the Clash five months earlier in London, when the scraggly punks showed up at an Ely gig at the Venue and then showed the band around London every night for a week. “I said, ‘if you ever come to Texas, we’d like to return the favor and show you guys around,’” recalls Ely. “They were all fascinated with Texas.” Joe Strummer called Ely a few weeks later and rattled off the cities the Clash wanted to play: Laredo, El Paso, Wichita Falls, the cities of cowboy movies and Marty Robbins songs. But first was the show at the Armadillo: the Clash’s Texas debut. “I remember we had to take the Clash tour manager Johnny Green to buy a toaster,” Ely says, when asked if anything unusual stood out about the show. “Beans and toast is all they ever ate.”

The Clash had just covered “I Fought the Law,” written by Lubbock native Sonny Curtis, first recorded by the Crickets and made famous by El Paso’s Bobby Fuller Four. So they spent three days in Lubbock after their Oct. 7, 1979 show there immersed in West Texas music history. “I took ‘em out to Buddy Holly’s grave and we stayed there all night,” says Ely, “just talking about music and singing songs.” The Joe Ely Band flew to London in February 1980 to open the Clash’s London Calling tour (cut short when drummer Topper Headon broke his hand) and the bands stayed close through the years. In fact, Ely and Strummer had planned to go to Mexico to make an album together when the punk icon died suddenly in 2002 from an undiagnosed heart defect.

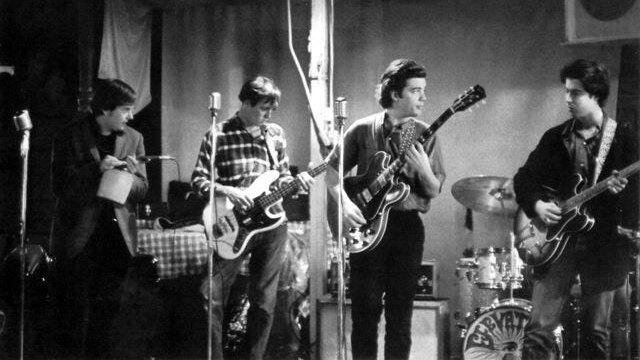

#13 Thirteenth Floor Elevators at New Orleans Club March 16, 1966

Elevators L-R Tommy Hall, Benny Thurman, Roky Erickson, Stacy Sutherland at the New Orleans Club 1966. Photo by Bob Simmons.

Austin’s acid rock pioneers were formed in the wake of Bob Dylan’s electric performance at Municipal Auditorium in September 1965. Two months later, U.T. student Tommy Hall, who managed a skiffle group called the Lingsmen, caught a set by Roky Erickson and the Spades at the Jade Room on San Jacinto St. near Scholz Garten. The Lingsmen had started to go electric, but lacked a singer who could break through the racket. Hall lured the Little Richard-screeching Erickson into the lineup and called this new “psychedelic rock” group the 13th Floor Elevators. They were almost immediately popular doing covers of the Rolling Stones and Buddy Holly, then really took off regionally after re-recording one of Roky’s Spade songs “You’re Gonna Miss Me” as their first single. Hall was a bit of an LSD guru, which attracted the attention of police and on Jan. 27, 1966, APD raided Hall’s house on E. 38th St., as well as the room in the Bel Air Motel where guitarist Stacy Sutherland and drummer John Ike Walton lived. They were all charged with drug possession and criminal conspiracy after marijuana was found.

Suddenly, local rock station KNOW stopped playing “You’re Gonna Miss Me” and the Jade Room declined to book the band as they awaited trial. But Roky had a former Travis High classmate who wanted to help. Bill Josey Jr. went by DJ Rim Kelly on KAZZ, a former jazz station owned by the Big 4 Mexican restaurant chain and run by Bill Josey Sr., the future owner of Sonobeat Records. The Joseys had been hosting live performances on the air from various clubs- Eleventh Door, Club Seville and Club Saracen- plus the New Orleans Club at 1125 Red River St. The N.O. Club didn’t have a stage, so they put a radio mike in front of blues singer/pianist Ernie Mae Miller. But Josey Jr. changed all that by booking the Elevators, who embraced the N.O. as their homebase club.

The bust had reminded the band how precious was their freedom, so the Elevators started working hard on new, original material, thinking more about posterity and personal artistry than the desires of dancing kids. The 30-minute show from March 16 has become a favorite bootleg of fans wanting to hear the first sparks of a remarkable three-year career before drug busts, delusions and paranoia brought down Austin’s greatest ‘60s rock band. Many Rokyphiles consider this first live recording to also be the band’s best, with the seven-minute cover of “Gloria” and the new original “Roller Coaster” (inspired by the dips and hills of 38th St. near Hancock Golf Course) easy highlights.

The live recording series was short-lived. Monroe Lopez sold KAZZ to KOKE AM in 1967 and it became KOKE FM the next year.

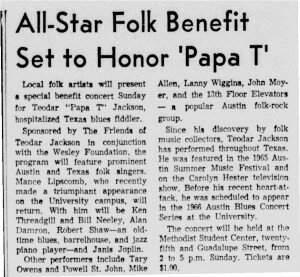

Just four days before the New Orleans Club live radio show on March 16, 1966, the Elevators and Janis Joplin shared a stage for the first and only time, according to the rather thorough band bio Eye Mind. It was at a benefit for black fiddler Papa T at the Methodist Student Center at UT, booked by Joplin’s Port Arthur pal Tary Owens, who was the person who took Tommy Hall to see Roky sing. There has been talk of Janis pondering an offer to join the Elevators as a second singer. I don’t know about that, but after she moved on to San Francisco, where she’d soon be the queen of hippie blues, there was a definite Roky-esque influence on her singing. The autoharp stayed behind.

“God, I wish there were live recordings of the Elevators during that period,” Owens said in a ‘70s interview. Then this tape surfaced to back him up.

#14 King Sunny Ade at Club Foot January, 1983

A star in his native Nigeria since the ‘60s, the king of African juju music signed to Island Records in ’82 and embarked on a 22-city tour of the U.S. with a huge promotional push. Thanks to Dan Del Santo’s “world beat” radio show on KUT, plus Talking Heads foray to the Dark Continent beat, Austin had a small, but devoted audience for African music at the time, so Brad First booked the guitarist/bandleader for about $7,500. Club Foot held 900, so they’d practically need to sell out at $10 a ticket to make any money off the show. And since there’d never been an “Afrobeat” show in Austin before, there was potential for disaster. “The owner fired me after that booking,” said First. The club had steadily been losing money and closed soon after the management change in late ’83. First said he was given a month’s notice and during that time he had the satisfaction of watching the King Sunny Ade show sell out (“thank you, UT African Students Union”) and leave the crowd gasping in ecstasy after two solid hours of O.G., original groove music.

The Afro-party moved to Liberty Lunch, where King Sunny packed the place a few more times, plus his mentor, the great Fela, played the Lunch at least twice. Fela first played Austin at the City Coliseum in ’86, on a show co-promoted by Louis Meyers. “There were no dressing rooms at the Coliseum, so we had to put the band in a big bathroom,” recalls Meyers. “And Fela came out of there and said, ‘You do not put FELA in a shithouse!”

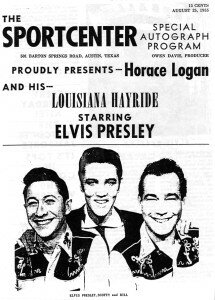

#15 Elvis at the Sportcenter Aug. 25, 1955

Billed as the “Folk Music Fireball” by an Austin promoter, Elvis Presley played three shows in Austin in 1955- at Dessau Hall in March, the Sportcenter in August and the Skyline Club in October- before his January 1956 national TV debut made him a sensation. The middle show is most noteworthy because it happened in the building, which, 15 years later, would house the Armadillo World Headquarters. Backed by guitarist Scotty Moore and bassist Bill Black, with no drums, Elvis headlined a Louisiana Hayride package show at the Sportcenter, named so because boxing and wrestling was held there. “Honky Tonk Man” Johnny Horton was also on the bill.

At his Austin debut on St. Patrick’s Day at Dessau, Presley drew only about 75 fans. The only DJ in town playing his records “That’s All Right, Mama,” “Good Rockin’ Tonight” and “Milk Cow Blues Boogie” was KVET’s R&B jock Lavada “Dr. Hepcat” Durst, so most folks thought Elvis was black. White kids didn’t go to black shows in 1955 and blacks didn’t go to Dessau Hall in far North Austin.

Five months later, however, Presley packed the 1,500-capacity Sportcenter on the heels of new single “Mystery Train” and frantic word-of-mouth. Austin watched him go from unknown to stardom in 1955.

#16. Daniel Johnston at MTV’s “Cutting Edge” taping August 1985

Daniel Johnston plays for MTV. Photo by Pat Blashill.

Glass Eye starting bringing this kid up before they went on, to play three songs. Always three, and the moptop would proudly tell you that he just made $15, more than he’d made for working as a McDonald’s janitor that day. He handed his crude, homemade tapes, bought in bulk from Radio Shack, to every pretty girl or connected-looking guy on the Drag, so it wasn’t long until everyone on the scene knew about him. The sweet, crazy guy with the awful music who thinks he’s the new Beatles. That was one faction. But Daniel Johnston also had his diehard fans who thought he was a genius. That’s the side that ended up winning the debate.

Turns out that after you got over that childlike, off-key warbling and primitive guitar strumming, the songs were heartbreaking symphonies of depth and meaning. Zeitgeist started covering “Walking the Cow,” Yo La Tengo played “Speeding Motorcycle” live and Kurt Cobain wore a Daniel Johnston “Hi How Are You?” t-shirt on the cover of Rolling Stone. Daniel became the Dylan of the Lo-Fi movement and now he’s probably a millionaire, though he has to live with his parents.

But when MTV came to town in the summer of 1985 to devote an entire hour to the Austin scene, Daniel Johnston was not one of the acts considered for a live taping. The show’s focus was on the post-“Murmur” guitar bands like True Believers, Doctors’ Mob, Zeitgeist, Wild Seeds and Dharma Bums plus there was some punk, some roots and Timbuk 3. Zeitgeist threw a barbecue for MTV cameras to get candid shots of bands hanging out and there was Daniel with his “Hi How Are You” aural business card, of course. “We’re having a conversation on MTV,” he said to the cameras and the director and crew fell in love with this sweet naïve.

Johnston was added to the big taping at Liberty Lunch and you really didn’t know if he would crumble under the pressure. Back then none of us knew the strength of his ambition, but he rose to the moment on “I Live My Broken Dreams,” with its great line equating a nervous breakdown with having a flat tire on Memory Lane. He can’t ignore the camera at the Lunch and can’t stop the grin that knows it’s all about to change.

Some Danielphiles would choose his triumphant appearance at 1990 Austin Music Awards. Johnston had gone around the bend for good, it seemed, after taking mushrooms at Woodshock 1986 and the next few years were mentally tumultuous, even as Johnston’s name grew in fame. He was greeted ecstatically at the AMAs and as he basked in the adulation it seemed his comeback was on. But the next day, Johnston had an episode of delusion and paranoia on the family’s small plane causing his father, a former Air Force pilot, to crash. They walked away with minor injuries, but Daniel, who became the subject of the award-winning documentary The Devil and Daniel Johnston, was committed for a time.

Personally, I prefer the moment when his broken dreams started coming true. Here was an artist who sprouted in Austin’s warm embrace. If there was ever a moment when Austin was the coolest music city in the universe, it was when Daniel Johnston stepped up to that mike in a jam-packed Liberty Lunch and nobody laughed.

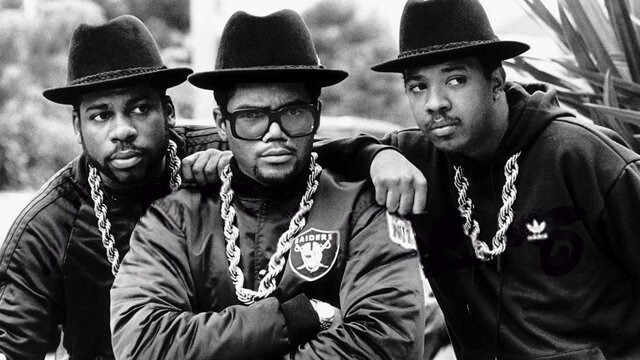

#17 Run-DMC at Liberty Lunch June 19, 1985

The Beastie Boys opened for Madonna at the Erwin Center six weeks earlier (and were booed off the stage), but the new era of hip-hop drew delirium and a few hiccups when Run-DMC played at Liberty Lunch on Juneteenth, June 19, 1985. This was a year before Raising Hell and its Aerosmith collab on “Walk This Way” drew down the bridge between rock and rap, but Run-DMC had already become the first hip hop act to record a million-seller with King of Rock. Joseph “Run” Simmons, Darryl McDaniel and Jam Master Jay played Austin on a day off from the Fresh Festival, hip hop’s first national package tour, which they headlined. They were taking off!

So it must’ve seemed strange when Harold McMillan of the sponsoring Black Arts Alliance picked up the trio at Robert Mueller Airport with his beat-up Datsun B-210 and took them to the seedy Stars Inn Motel on I-35 near 32nd Street. “They were saying ‘Hey, man, this ain’t in our rider,’ but I had to tell them we were just a broke black arts organization,” McMillan recalls. The BAA paid Run-DMC $5,000 and ended up making a profit of $6,000 on the $10 show, according to the 1985 financial report kept at the Austin History Center.

McMillan’s Datsun with the holes in the floorboard wasn’t the lowest ride the rap icons took during their 24 hours in Austin. When they showed up at Liberty Lunch before the show, they realized that they’d left their records on the Fresh Fest tour and enlisted co-promoter Louis Meyers to take them to the record store, pronto. Meyers took them in a pickup to Sound Warehouse on Burnet Road so they could buy vinyl to rap over. “They just climbed in the back of the pickup and we were off,” says Meyers.

The sold-out crowd of 1,200 was about 50/50 black and white- unheard of in Austin at the time- and they were united in ecstasy when Run-DMC charged out onto the stage. Only problem was that the plywood Liberty Lunch stage had some play in it and every time one of the rappers jumped or even stepped hard, the record would skip. Jay was doing his best to keep the beat going, but it soon became apparent that the only way to save the show was for Run and DMC to be as stationary as possible. They did a lot of that folding arm pose.

It was a thrown-together benefit for an arts organization, but the Run-DMC show is significant for validating hip hop as a live music event to the rock crowd. This wasn’t held at some dance club on Sixth Street, but the proving grounds of Liberty Lunch. Back in 1985, five years after Sugarhill Gang headlined at Palmer, people still didn’t know if rap was more than a fad. When you felt the power of Run-DMC live, you knew it was here to stay.

#18 Buck Owens Birthday Bash at the Continental Club August 12, 1995

Buck Owens stunned the crowd when he showed up for his birthday bash at the Continental. Casper Rawls on guitar. Photo by Martha Grenon.

Austin is a Buckaroo town, more Bakersfield than Nashville, so it was natural that local musicians do a tribute night to the ‘60s honky tonk hero whose twangin’ #1s include “Act Naturally,” “Sam’s Place” and “Waiting In Your Welfare Line.” Guitarist Casper Rawls, then of the Leroi Brothers, and drummer Tom Lewis of the Wagoneers, put the first Buck Owens Birthday Bash together in 1992 and the show was such a blast that it became an annual Continental Club event. Every Travis County country musician of note put it on their calendar and, as a courtesy, Rawls invited Owens, a native of Sherman, Texas, every year.

And in the fourth year, the country legend showed up. Only four people from the club- Rawls, Lewis, clubowner Steve Wertheimer and singer Kelly Willis- knew ahead of time that it was going to happen and even they weren’t 100% until Owens came in the front door about an hour into the show. Wertheimer whisked the ultra-special guest to a roped-off spot at the corner of the bar, but he’d been spotted and it shot through the crowd: “Buck Owens is in the house!”

The seed was planted a year earlier when Owens, deeply touched by the birthday tribute, sent Rawls one of his red, white and blue guitars. On the pick guard Owens had engraved “To Casper, I might see you August 12, 1995!” Buck’s private plane was enroute to Austin that day, with singer-songwriter Jim Lauderdale and Buckaroos pianist Jim Shaw along for the jam.

After checking things out for a bit, Owens took the stage to sing a duet with Kelly Wills on “Loose Talk” and the crowd went nuts. Later Owens joined Rawls and the house band for three numbers: “Love’s Gonna Live Here,” “I Don’t Hear You” and “I’ve Got a Tiger by the Tail.” A birthday cake and a raucous singalong of “Happy Birthday” followed. It was a party no one present would ever forget.

Lewis says one of the night’s moments that stays with him came late in the show, when Buck came from his stool in the back corner to the side of the stage to watch the Derailers, who wore matching suits like the Buckaroos and modeled their sound after the Telecaster-driven band from Bakersfield. As Tony Villanueva and Brian Hofeldt tapped into the chemistry of Owens and his musical soul mate Don Rich, Buck had tears in his eyes.

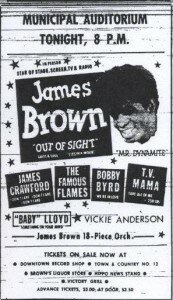

#19. James Brown at Municipal Auditorium Aug. 1, 1966

Tim Hamblin of the Austin History Center found this ad, which ran in the Statesman on August 1, 1966, after watching an interview James Brown did with an access TV show in 1982.

If that date looks familiar that’s because it was the day UT engineering student Charles Whitman killed 11 people from the observation deck of the UT Tower, after killing three on the way up. JAMES BROWN PLAYED AUSTIN ON THE NIGHT OF THE SNIPER MASS MURDER! You would think that would be a substantial event, except that, until last year, hardly anybody had even known about it. This wasn’t like the night Martin Luther King Jr. was assassinated and the James Brown show went on to quell rioting in Boston. There had been absolutely no trace of this concert in Austin lore until Tim Hamblin, a video archivist for the Austin History Center, was going through some old footage from 1982 at Club Foot and found an interview with James Brown. Asked if he’d ever played Austin before, the Godfather of Soul said, “Yeah, I played here the night that guy went crazy up there on the tower!” Hamblin had never heard that before. Intrigued, he went searching for a newspaper ad for the show and found one in the Statesman.

The next question was “Did the show go on?” That brought me to the Austin History Center last year to peruse copies of the Capital City Argus, Austin’s black newspaper of the time. There I found a review of the Monday Aug. 1 show written by “Roving Eyes,” which is one of the pseudonyms Bert Adams used. According to the review, James Brown sat in with the 18-piece band for about half an hour on organ before he took the spotlight. Nowhere in the review did it mention the day of terror, which began just 11 blocks from Municipal Auditorium (later renamed Palmer) at the Bouldin Creek house at 906 Jewel Street, where Whitman stabbed his wife to death while she slept.

Austin was pretty much segregated in 1966 and what happened over at the white college didn’t affect the goings on in the black community. So, although it’s a tad surprising the review didn’t mention 16 murders in town that day, it’s not a shock. “Those of you who had to pay $3.00 or $3.50 can say it was well worth it,” the review concluded. “James Brown, gold suit and all, is out of this world.”

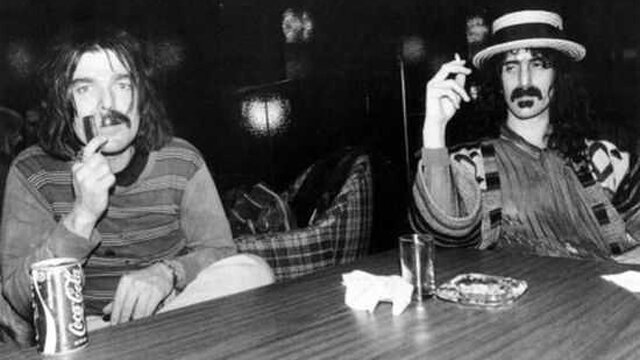

#20 Frank Zappa with Captain Beefheart at the Armadillo World Headquarters May 20 & 21, 1975

The most legendary of all Austin music venues was adopted by many acts during its run from 1970-1980: Freddie King, Willie Nelson, Commander Cody, Bruce Springsteen and on and on. But there was no stronger allegiance to the ugly building at 525½ Barton Springs Road than from Frank Zappa, whose lyrics often satirized the counterculture and yet he had true affinity for the ‘Dillo tribe. He even wrote a verse about the Guacamole Queen and “her aura” for his song “Inca Roads,” from One Size Fits All in 1975. “He played so often that we had to rotate the artists who did the posters and they all seemed to get a crack at Zappa,” says former Armadillo owner Eddie Wilson. The first time rock’s weirdo composer (and great guitarist) played the ‘Dillo, in ’72, there was a bomb scare in the middle of a song and, after the evacuated fans were returned to the hall an hour later, Zappa struck up the band at the exact point in the song where the concert had stopped.

But none of Zappa’s shows at the ‘Dillo stand out this many years later like the two nights that were recorded for Bongo Fury, the last Zappa album with the Mothers of Invention as his band’s name. That 1975 album, released just five months after the Armadillo shows, was notable because it reunited Zappa and his former Antelope Valley High School (Lancaster, Cal.) classmate Don Van Vliet, better known as Captain Beefheart. The two avant-gardians of the hippie era had huge influences on each other growing up and Zappa produced the Beefheart masterpiece Trout Mask Replica (1969), but the Bongo Fury tour was the only time Beefheart went on the road with Zappa. The album also marks the first appearance of Terry Bozzio, Zappa’s late ‘70s drummer, who now lives in Austin, as original Mothers drummer Jimmy Carl Black once did.

“Zappa was a compulsive perfectionist,” recalls Eddie Wilson. “Our crew worked their asses off for him. I think that’s one of the main reasons he liked the Armadillo.” But Zappa was also able to adapt on the fly. For one show his contract stipulated that he’d have four hours to rehearse and a full hour soundcheck before the doors opened at 7 p.m. Except that Zappa’s equipment trucks didn’t arrive until 5:30 p.m. and he had only 15 minutes to soundcheck. “Zappa walked off the stage really pissed off and I said, ‘I know the last thing in the world you want to do right now is meet anybody, but you’ve got a blind, deaf and crippled guy opening for you and I’ll take you over to meet him if you’d like.” Zappa and Blind George McClain hit it off and Zappa took the Split Rail regular out on the road with him.

Of the nine tracks on Bongo Fury, six and a half were recorded at the Armadillo, including the Van Vliet compositions “Sam with the Showing Scalp Flat Top” (the title Bongo Fury comes from the lyrics) and “Man With the Woman Head.” The concert ends with Zappa saying what’s become a local catchphrase: “Goodnight Austin, Texas, wherever you are.” Beefheart passed away in 2010 after a long battle with multiple sclerosis. Zappa died in 1993 from prostate cancer.

#21 Gang of Four at Club Foot Nov. 4, 1980

Gang of Four, shown here in NYC, played in Austin on the night Ronald Reagan was elected president.

On the night of November 4, 1980, Ronald Reagan was declared the winner of the Presidential election and the politically-radical Gang of Four took the stage at the jam-packed club on 4th and Congress. The juxtaposition of these two events made for two hours that no one there would ever forget. After reminding the crowd of the world in trouble they were in with Reagan in charge, Gang of Four firehosed the room with danceable punk rock that left everyone dripping. “It was one of those great rock shows that crosses the line into pandemonium,” said photographer David C. Fox. “You know that saying about how ‘rock and roll saved my life’? That’s how that night felt.” This list is not a ranking of the greatest concerts the town’s ever seen. We’re not counting encores, this was one of those truly musical intense shows that came out of a big moment. Context. The lines were becoming clearer that night and the Gang of Four made their side the one to be on.

#22 The Standells at Big Mamou 1987

Impostor Jimmie Lee Dean and the real Dick Dodd. Photos by Theresa DiMenno.

This was the night Austin caught an impostor and threw his ass in jail, while the guy he was playing stepped in and finished the show. Steve Chaney had booked a band billing themselves as the Standells of “Dirty Water” fame, with original member Dick Dodd in the group. But when “Dick Dodd” showed up for a radio interview, a local music journalist in the studio knew that wasn’t the real one and told Chaney, who asked for the real Dodd’s number. It turned out Dodd, who lived in California, hadn’t received any royalties in two years and suspected that someone had been cashing about $15,000 in checks. Dodd flew to Austin later that night and notified the Austin Police Department of the fraud. Five officers were sent to the S. Congress Ave, location currently home to C-Boy’s. The fake Standells played one song, a metal version of “You Really Got a Hold On Me,” then the lights came up and the cops took it from there, arresting 36-year-old Jimmie Lee Dean of Houston. About half the audience was in on what was happening and back then there was no social media to tip off the perps. As one officer led away Dean in handcuffs, the path crossed with the man whose identity he had taken. “Dick Dodd,” said the officer, “meet Dick Dodd.”

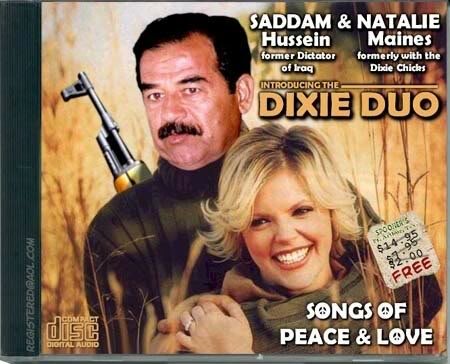

#23 The Dixie Chicks at Erwin Center May 2003

Toby Keith’s evil photoshop.

You know what happened. Chick spoke out. Country music audience boycotted. The Austin-based Dixie Chicks had just become the best-selling group in the history of country music, averaging 10 million copies sold. And then they were history. But before Natalie Maines told a British audience that the Dixie Chicks were ashamed that the president was from Texas, they had sold out many shows in the U.S. tour, including a return home May 21, 2003 at the Erwin Center. Protests greeted most shows and a few, put on sale after the incident, were canceled for slow ticket sales, but Maines was not ready to make nice. One song from the performance at the Drum was aired live on the Academy of Country Music Awards, which is why Natalie was wearing a shirt with the initials FUTK, for “Fuck You Toby Keith.” Keith had been screening a photoshopped image of Maines and Saddam Hussein as lovers during his shows. Classy.

Natalie’s response.

Turns out Maines was right about Iraq, but most American country music fans have still not forgiven the Dixie Chicks, whose touring these days is limited to Canada.

#24 AC/DC at the Armadillo World Headquarters July 27, 1977

AC/DC on the 1977 tour.

The Australian riff maestros were big back home, but had yet to conquer the States when Atlantic Records booked them to play a club tour to promote Let There Be Rock. They were so unknown in the U.S. at the time that AC/DC opened for Canadian band Moxy on four Texas shows promoted by Stone City Attractions of San Antonio. In a 1995 interview with guitarist Angus Young, he told me how the Austin show became their first-ever concert on American soil. “We were supposed to play in Phoenix the night before, but Bon followed a girl off the plane in L.A. and he missed the flight.” The setlist for their U.S. debut at the ‘Dillo was “Live Wire,” followed by “She’s Got Balls,” “Problem Child,” “Whole Lotta Rosie,” “Dog Eat Dog,” “The Jack” and “Baby Please Don’t Go.” That Chuck Berry metal, with Bon Scott’s vocals slicing through stole the show no doubt. The next time AC/DC came to Austin, in July ’78, they headlined a sold-out show at Willie’s Austin Opry House on Academy Drive.

#25 Freddy Fender at Soap Creek Saloon 1974

When Freddy Fender, working as an auto mechanic in Corpus at the time, pulled into the parking lot of the original Soap Creek Saloon, in the hills of Westlake, he wondered what that crazy guero Doug Sahm had gotten him into. The parking lot of the wooded hideaway was filled with longhairs in cowboy hats passing around joints. What the hell…

But Sahm had sparked interest in the man born Baldemar Huerta when he covered Fender’s “Wasted Days and Wasted Nights” on his 1971 Tex-Mex roots project The Return of Doug Saldana. The track opened with a Sahm salute: “And now a song by the great Freddy Fender. Freddy, this is for you, wherever you are.” A teenaged Sahm used to follow “El Be-Bop Kid,” as Fender was billed in the late ’50s, but after Fender went to prison for marijuana possession in the ‘60s, his career was untracked. To ensure a crowd, Sahm opened the Soap Creek show, then joined Fender on a couple songs, a vocal combo that would play out two decades later with the Texas Tornados. Fender’s mix of gritty bar band rockers and romantic bilingual ballads were greeted by stoned jubilation from the audience, convincing Fender to re-focus on his musical career. He reconnected with producer Huey Meaux, who convinced him to cover a country song “Before the Next Teardrop Falls” in his quivering vibrato. Released in January 1975, the song became a #1 smash, not only on country, but pop charts. The followup was a re-recording of “Wasted Days,” which also hit #1. Suddenly, the lisping mechanic was the hottest “new” singer in the country, being named Billboard magazine’s male vocalist of 1975. “Teardrop” also won that year’s CMA award for single of the year, but if not for what happened at Soap Creek, Fender might’ve still been fixing cars and playing dive bars in the Valley on weekends.

Pingback: AC/DC: Austin first US show - MarshallForum.com()

Pingback: ()

Pingback: ()

Pingback: 25 Sidebar: “Just Notorious, Not Significant” | ArtsLaborAustin()

Pingback: ()