What’s the album that changed your life? The one that reconfigured the chromosomes to unlock a whole new world of possibility?

Hearing More of the Monkees– over and over and over again- at age 11 made me love rock music. ABC by the Jackson 5 gave my ears their first orgasm.

Hot Rocks by the Rolling Stones led to Lou Reed’s Rock and Roll Animal and then to Patti Smith’s Horses to make the freak transformation complete. No straight life for me.

But the album that changed my life in more concrete ways because it changed my work was a quickie British compilation of black singers, shouters and preachers from the 1920’s – a flimsy package with no pictures or liner notes. Sometimes it’s a knockoff that knocks you out. Amazing Gospel, which came in the mail to my job at the Austin American Statesman in July 2001, provided the first time I would ever hear the music of Arizona Dranes, Washington Phillips and Blind Willie Johnson, the holy trinity of the Texas gospel music pioneers, whose biographical blanks I would spend chunks of the next 15 years trying to fill.

But the album that changed my life in more concrete ways because it changed my work was a quickie British compilation of black singers, shouters and preachers from the 1920’s – a flimsy package with no pictures or liner notes. Sometimes it’s a knockoff that knocks you out. Amazing Gospel, which came in the mail to my job at the Austin American Statesman in July 2001, provided the first time I would ever hear the music of Arizona Dranes, Washington Phillips and Blind Willie Johnson, the holy trinity of the Texas gospel music pioneers, whose biographical blanks I would spend chunks of the next 15 years trying to fill.

Doing primary research on unsung musical trailblazers turns me on like nothing else, which is pretty sad, but what are you gonna do? When I start to feel overcome with emptiness I head to one of the great history centers in town (The Dolph Briscoe Center for American History on the UT campus is a favorite) and run my fingers through dusty pages. Whoever said everyone will eventually find a soulmate was right.

I made my reputation in this town by butchering sacred cows, writing some things that, looking back, I’m not so proud of. I was just trying to be funny. My whole writing voice comes from guests I used to watch on the Johnny Carson show every night when my mind was forming. Hemingway? Vonnegut? Kerouac? My style is inspired by Rex Reed, Don Rickles and Paul Lynde in the center square. And I can’t forget professional wrestlers Ripper Collins and Mad Dog Mayne, who baited audiences in my hometown of Honolulu every Saturday.

It always felt weird judging music when I didn’t know anything about how it was made. That side just never interested me. I’m just a fan who could write a little and so I always tried to suggest right up front that “warning: what follows could be complete bullshit.” But maybe you’d get a laugh. A roast comic with stage fright- that’s me.

My weakest characteristic as a critic? I never much liked to listen to new music. Now, I’ve spent a lot of time and money getting into the best headset to appreciate an album or concert that I’ve had to review. I want to give the musicians every advantage before I write that they’re bad enough to drive a pimp off a payphone. (Boy, is that line dated!) But I kinda felt like a dick sometimes. I wanted my byline to read “by Michael Corcoran, who once camped out for Elton John tickets.” Before you read this Wavves review, please be aware that last week, when the writer’s neighbor banged on his RV because the music was too loud, he was cranking “Yellow” by Coldplay.

I’ve known that I was a fraud from the very start, but what am I supposed to do? I had this job. It was easy and I was good at it. But I never took myself seriously and was fine with letting everyone know I was full of shit. I once wrote that Oasis in 1995 was better than the Beatles in 1965. And I believed it at the time.

Don’t be afraid of being wrong. That’s the advice I’d give to any aspiring music critic. It’s better than being boring, like all those musically correct hacks out there trying to come off hip by writing how country music today just sounds like bad rock and EDM isn’t really artistry as much as computer programming. Ruled by the comments section.

The job of rock critic is totally unnecessary, especially now when consumers have instant access to the same music as critics do. The justification for hiring music critics used to be that they would listen to everything and then pass on the thoughts and recommendations to the record-buying, concert-going public. And now they come up with lists like 25 Bands That Got Better After a Founding Member Was Replaced. In these days of snark, Pete Best gets written about more than the Beatles.

A knock on me is that I’m a contrarian, which I won’t deny. But the motivation is not to inspire uproar. It’s to be read. It’s to present a fresh take on an overworn topic. There’s so much phoniness out there, especially in hip cities like Austin and Portland. Shut up and show your work. And I’ll let you know if I think it’s any good (it’s not.)

I was more than ready for my second career as a music historian to come around. To my thinking, preserving history is a higher calling for a music critic than assessing the newish sounds. Obscurity is a greater injustice when the artist is dead, instead of on a small indie label.

After hearing Amazing Gospel, I was driven by the supreme talents of those long-gone Texans Dranes, Johnson and Phillips, whose pioneering work continues to inspire musicians today. In all three cases, just finding the death certificate tripled the previously known biographical information. Someone told me I was doing “primary research,” which I soon realized meant caring about something no one else does. It’s a puzzle and the pieces have been scattered all over Texas.

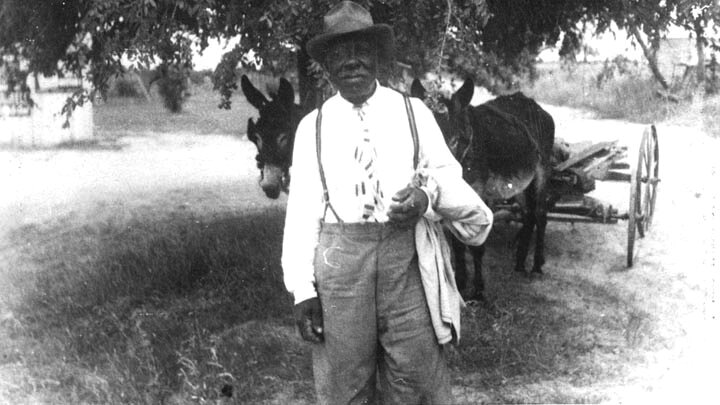

Washington Phillips at around age 70, 1950.

Washington Phillips was the first of those subjects I delved into. I was drawn by the mystery of how an East Texas farmer could create such mesmerizing recordings. I’d never heard anything like it. Some misinformation on liner notes had Phillips dying in Austin in 1939, which gave me the local angle to satisfy my editors at the Austin American Statesman, but then the story changed. I went rogue on this one, not telling anyone where I was, with the story or physically, until I’d finished the first draft. One day I was in my car chasing a hot tip to Freestone County- about 70 miles east of Waco- when an editor called to tell me that Clifford Antone had just been released from prison (on marijuana charges) and I needed to write a story. “I’m out of town on that Wash Phillips story,” I said. “I can’t do it.” The editor said I needed to come back. “No way,” I said. I was about to crack a case of mistaken identity. Here’s my story on Washington Phillips.

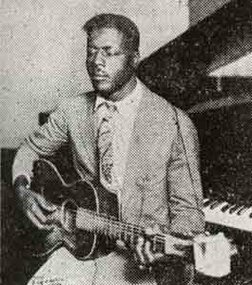

Only know photo of Blind Willie Johnson.

After my Phillips piece was reprinted in the Dallas Observer, I received a note from a guy up there named Dan Williams, who said I should consider also writing a story about Blind Willie Johnson, the great bottleneck player from Marlin. Johnson recorded 30 tracks from 1927- 1930, then fell into my wheelhouse- off the face of the earth. In the 1970s, Williams visited Marlin looking for anyone who knew Blind Willie and ended up finding his ex-wife Willie B. Harris. Up until that time, it was believed that Johnson’s second wife Angeline sang on his records. That’s what she told blues historian Sam Charters in the late 1950s. But after hearing Harris sing, Williams correctly determined that she was the one who had nursed Johnson’s coarse, raw bass vocals in call and response style.

Williams passed on an interesting bit of information: Blind Willie Johnson’s daughter Sam Faye Kelly was back living in Marlin. This was huge. Maybe she had a photo of her father (who died in 1945) or church programs on which he played. I drove up and met her a few times, found that she had nothing but unspecific memories, and ended up writing this story for the Statesman.

Both my Wash Phillips and Blind Willie Johnson stories were selected for the Da Capo “Best Music Writing” of the year anthologies. And both are chapters in my 2005 book All Over the Map: True Heroes of Texas Music (UT Press). That left just one.

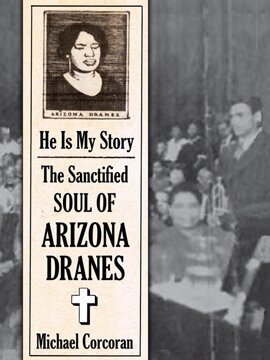

Arizona Dranes at the piano, 1944.

I first heard about Arizona Dranes, who introduced such secular piano styles as ragtime and barrelhouse to gospel music in 1926, when I was researching a story on Fort Worth gospel phenom Kirk Franklin and the group God’s Property in 1997. I bought a history of gospel called How Sweet the Sound by musician/ historian Horace Boyer, who credited Dranes with inventing “the gospel beat.” That’s another way of saying soul music.

I had two swipes at researching and writing about Dranes, who was educated at the Texas School for Deaf, Dumb or Blind Colored Youths in Austin from 1896-1912. Then Josh Rosenthal of Tompkins Square Records hired me to write a 52-page CD booklet to go with a reissue of Dranes’ 1926-1928 recordings. That combo of words and music called He Is My Story: The Sanctified Soul of Arizona Dranes was nominated for a Grammy as best historical album in 2013. Here is a condensed version of the history.

A writer wants to leave a mark and mine won’t be the three years I terrorized local celebrities with my “Don’t You Start Me Talking” column in the Austin Chronicle (1985-88). It’ll be my research of three Texas musicians who made a blip in the 1920s and then disappeared. I found them in death certificates and city directories and school enrollment records and told their stories, sometimes assisted by folks who knew them.

When I started writing for the Austin Chronicle I was 29 and going to live forever or die tomorrow. Didn’t matter. But now I want at least some of my work to remain long after I’m gone.

This past summer I finished a project I began 12 years ago, a book about Washington Phillips, with all sorts of new and exciting biographical information. (Well, at least they were to me.) I went to Freestone County, where Wash Phillips was born and died, at least half a dozen times, but I looked forward to each next visit like other folks anticipated a trip to Hawaii.

Look for Washington Phillips and His Manzarene Dreams, a book/CD like the Dranes package, on the Dust-To-Digital imprint late in the year. And try and catch The Jones Family Will Make a Way documentary, about my favorite current gospel group, at SXSW in March.

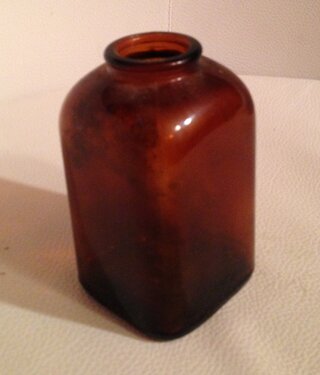

Washington Phillips’ snuff bottle.