Mike Flanigin at the Continental Gallery, where he plays every Friday and Saturday night.

Mike Flanigin was a guitar player, a real good one. In 1992, the Denton native toured the country with the Red Devils, the L.A.-based blues band whose debut King King was produced by Rick Rubin. After the Devils broke up in ’94, he moved to Austin because this is where guitar players go to chase work and tail and, maybe in the process, get a real education.

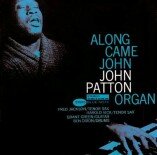

And then one night at Antone’s, in the corner of his eye, he saw the Hammond B3. Flanigin was playing an organ song- Big John Patton’s “Let ‘Em Roll”- on a steel guitar and he asked himself why wasn’t he playing it on that B3? Which was all it took. The first time Flanigin pressed his fingers down on the B3, he was no longer a guitar player. “Even when I didn’t know how to play, I knew this was the instrument I was meant for,” he said from the 1960’s house he rents in Rollingwood. “The B3 required all my attention, so I didn’t have time for the guitar anymore.” You don’t dabble with that four-legged cabinet that holds an empire of sound- it takes over your life.

Flanigin’s debut solo LP The Drifter, which comes out August 21 with special guests Gary Clark Jr., Billy Gibbons, Kat Edmonson, Jimmie Vaughan, Rev. Gean West and Alejandro Escovedo, is the culmination of two decades of learning how to lock it down on the B3. But it also tells the story of his life in lyrics that this son of an Air Force pilot has been accumulating through his travels in the wild blues yonder. The title track of The Drifter is a Gatemouth Brown cover sang by Gibbons, but the other nine songs are Flanigin originals.

When he was still quite green, with his only organ experience in Doyle Bramhall Sr.’s band for a few months, Flanigin opened for B3 kingpin Jimmy Smith at the Mercury. Considering that Smith had recorded nearly 40 classic soul-jazz records for the Blue Note and Verve labels beginning in 1956, this would be like opening for Richard Pryor with knock-knock jokes. But Flanigin, then 32, got the gig because the club needed to provide a B3 and Flanigin had one. Luckily, this was the ground-floor version of the Mercury, not the one upstairs that’s now called the Parish, because hauling a 425-lb B3 and a Leslie speaker almost as heavy up a flight of stairs has caused many a roadie to consider another line of work.

Mike Flanigin in Marfa. Photo by Ashley McCue.

“I hoped and prayed that Jimmy Smith would show up right before he went on and miss my set,” said Flanigin, feeling insecure about his pairing with the absolute genius of grit n’ soul. “At one point I looked over and there he was. JIMMY SMITH WAS WATCHING ME PLAY THE ORGAN! I just froze up, man. I stopped playing,” Flanigin was able to compose himself after a long minute and finished the set.

The B3 actually belonged to Mike Judge, who Flanigin knew from Dallas, when the Silicon Valley creator played bass for Anson Funderburgh. Since Hammond stopped producing B3s in 1975, the organ had to be over 20 years old, but it had never been played in public when Judge bought it. Smith, who’d been playing every beat-up piece of shit organ the clubs provided on his tour, loved the pristine instrument.

After the crowd had cleared out, Smith went back onstage and sat at the organ. Flanigin was up there to get the B3 ready to move, but Smith motioned for him to sit next to him on the bench. And for the next 30 minutes, the master showed the novice a few things on the B3.

“I had heard that Jimmy Smith could be difficult and moody- that was his reputation,” said Flanigin, “but he was nothing but nice to me that night.” Flanigin would, a few years later, see the temperamental side of Smith, when the icon refused to go back onstage at Antone’s after the club’s B3 temporarily died on him. But that night at the Mercury was a magical experience that will stay with Flanigin forever.

“It’s all the blues, man,” Smith told the kid after one adventurous run. “I was thinking ‘that’s not like any blues I’ve ever heard,’” Flanigin said with a chuckle. The legend’s impromptu tutorial showed Flanigin just how much he had to learn.

Jimmy Smith

James Oscar Smith of Philadelphia started off as a piano player, but switched in 1953 when he heard Wild Bill Davis play the Hammond organ in Milt Larkin’s Houston-based big band. A key selling point for music school graduate Smith was that the organ never went out of tune. The first great electric organ player of note was piano legend Fats Waller, who grew up playing church organ at his father’s Abyssinian Baptist Church in Harlem. Waller taught Count Basie, who made the organ swing in the ‘30s. Chicago’s Les Strand earned the nickname “the Art Tatum of the organ” in the ‘40s and recorded with Coleman Hawkins, and there was also Smith’s Philadelphia neighbor Bill Doggett, who played a Hammond in Louis Jordan’s Tympani Five before forming his own band and having a smash with sax man Clifford Scott on “Honky Tonk (Pts. 1 and 2)” in 1956. But improvisational virtuoso Smith created much of the language of the Hammond B3 organ and anybody who’s played it after, even the rock and R&B players like Steve Winwood, Gregg Allman, Brian Auger, Keith Emerson, Jon Lord of Deep Purple, Greg Rolie of Santana, Felix Cavaliere of the Rascals and Booker T. Jones and Billy Preston, have got some Jimmy Smith in their heads. He is the Source, like T-Bone Walker on the electric blues guitar.

The B3 came out in 1954, just when Smith was starting out, and he pioneered the walking bass lines with his left hand and fleet-fingered single note runs on his right that emulated Charlie Parker. Smith’s hands clasped the relationship between the upper and lower keyboards, while his feet on the pedals colored the undertones like a mournful string bass. The 1956 LP, The Incredible Jimmy Smith, changed everything.

The Philadelphia area was as fertile for B3 players as Chicago was for electric blues guitarists, with Jimmy McGriff, Richard “Groove” Holmes, Charles Earland, Don Patterson and more coming from Philly and New Jersey. The Garden State is where Flanigin tracked down one of his favorite organists Big John Patton, in 1999. “As a blues guitarist coming up, almost all your heroes had passed away,” Flanigin said. “But when I really started getting into the B3, I found out that most of the greats who played on my favorite records were still alive.” He knew that if he was going to get better he had to apprentice with a total pro.

Big John Patton tutored Flanigin for almost two years.

Flanigin relocated to Boston at the turn of the 21st century when his wife at the time had a job there. Checking the New York City papers one day he saw an upcoming gig by Big John Patton at the Jazz Standard, so he took the train from Boston for the show. “He was a pretty dark cat, not really very approachable,” said Flanigin, but when it turned out that the older woman he’d struck up a conversation with was Patton’s wife Thelma, she introduced Flanigin to his hero. “I said, ‘I’d sure like to come to your house some day and learn a few things,'” Flanigin recalled, “and he said ‘sure, how ’bout tomorrow?'” Flanigin took the bus to Montclair, NJ, expecting to knock on the door of a mansion. After all, Patton, guitarist Grant Green and drummer Ben Dixon made some of the greatest jazz organ trio records ever at Blue Note in the ’60s. This man was musical royalty, so Flanigin was surprised to see the Pattons living in a one-bedroom apartment. Flanigin slept on the couch and every morning for a week, he woke up to Big John’s B3 sounds while Thelma cooked breakfast. “All John ever wanted to do was play,” said Flanigin. For ten hours every day, the jazz great would show the student some things, then watch him try them on his own. You can’t get training like that at music school.

Flanigin visited the Pattons regularly over the next two years, usually staying over for about a week at a time, before heading back to Boston. Some nights Patton took Flanigin to organ-centric jazz clubs in Harlem. “He’d say, ‘This is my man, Mike. He’s a great organ player,'” and I’d feel like a million bucks.”

Flan and the Man. Billy Gibbons sings the title track on The Drifter, which comes out in August.

Patton died in 2002 at age 66 from complications due to diabetes. His Hammond B3, which he bought in 1963 at Macy’s, sits in Flanigin’s living room. “We tried to get the Smithsonian to take it, but they wouldn’t, so Thelma gave it to me,” said Flanigin, who paid about $1,000 to have it shipped to him in Austin.

On a recent afternoon, Flanigin sat at Big John’s “desk,” which is what a lot of players call their B3s, and showed its features. Besides two 61-note keyboards, the organ has 24 foot bars, a volume pedal and 38 drawbars, also called “stops,” which a player can customize for his own sound. The term “pulling out all the stops” refers to an organ player who’s opened all the drawbars for crescendos. “It looks really complicated,” Flanigin said of the setup before him, “but it’s like driving a car. There are all those knobs and pedals, but after a while it becomes second nature.”

****

The electric organ was invented by Laurens Hammond of Evanston, IL in 1934 and advertised as an economical alternative to the massive pipe organs of churches, theaters and baseball stadiums. In that way, it was the first synthesizer. A non-musician, Hammond held 110 patents and had earlier invented an electric clock, which gave him his fortune, plus 3D movies and a card-shuffling contraption. Needing a new money-maker after the Hammond Electric Bridge Table ran its course, selling 14,000 units in two years, Hammond based the organ on the synchronized motor he used for his clock. He realized that it could produce tones that would never go out of tune. That was the gimmick, but Hammond’s accountant, a church organist, persuaded Hammond to go further and invent a new kind of electric organ. The sound on a Hammond is produced by 91 tone wheels, which revolve around a magnetic coil. Much of the appeal was that the keyboard action could be fast, like a piano, but it had the ability to sustain notes.

The B3’s AC signal created a pop sound with each keystroke, which rotating Leslie speakers were designed to smooth out. The tremelo effect added to the Hammond sound.

In 1935, the first year of production, Hammond sold 1,750 organs to churches, but also drew the attention of the Federal Trade Commission, which looked into a complaint by pipe organ manufacturers that Hammond was using deceptive advertising when it claimed that the $2,600 Model A could duplicate the sounds of a $75,000 pipe organ. A blind listening test was held and about 1/3 of the participants guessed that the Hammond was the pipe organ, which ended up being great publicity for Hammond.

Chicago-based Hammond introduced the BC model in 1936, the C model in ’39, the B-2 and C-2 in ’49 and the B-3 and C-3 in 1954. Besides churches, radio soap operas were early Hammond organ customers. Then, when Ethel Smith of Pittsburgh had a huge hit with “Tico Tico,” from the 1944 Red Skelton film Bathing Beauty, the home market exploded for Hammond, which produced the spinet organ in 1949.

Bobbie Nelson, who plays with her brother Willie’s band, got a job demonstrating Hammond organs in Fort Worth and paid the bills for years that way. Also up in Fort Worth in the late ’60s was Austin B3 favorite Red Young, “the Organizer,” who played organ on Wanted: The Outlaws in 1976, toured with Sonny & Cher, Dolly Parton and Joan Armatrading, recorded on sessions with Nelson Riddle and now plays all those great organ parts for Eric Burdon and the Animals. And we can’t forget Austin’s first great B3 player Dr. James Polk, who plays most Monday nights at the Continental Gallery with sax player Elias Haslanger.

During the ’70’s, jazz moved into a rock fusion sound that ditched the B3 in favor of clavinets, synthesizers and electric pianos. And the home market was taken over by cheaper digital keyboards. Hammond discontinued the B3 in 1975 and filed for bankruptcy 10 years later. But the B3 has gotten even hipper, especially after such acts as Medeski, Martin and Wood and Galactic introduced organ jams to festival crowds.

Hammond was bought by Suzuki Music of Japan, which produced a new B3 in 2009, but no self-respecting soul-jazz player would go for that digital model. Everybody wants to play what Jimmy Smith played. You’ve gotta have that attitude if you’re going to give your life to the B3. And this is the many-faceted instrument which is known to inspire such desire.

ORGAN PORN

- Flanigin said Dr. Lonnie Smith is perhaps the best B3 player working today.

- The King of the B3!

- Les Strand played a Baldwin organ with Coleman Hawkins.

- Leon Spencer Jr. of Houston made some great “acid jazz” records on the Prestige label.

- “This is probably my favorite B3 album” said Mike Flanigin.

- Milt Buckner was a jazz giant whose legs could barely reach the pedals.

- Mike Flanigin, 50, began his career as a guitarist.