Originally published March 2014

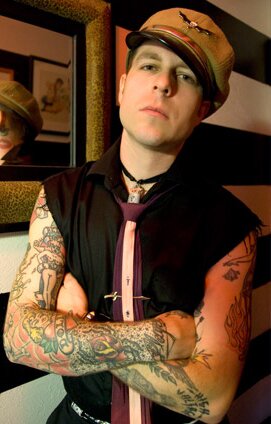

Some people are stars without being famous. Their talent shines so brightly and the way they carry themselves is so confident that destiny calls their name. Nick Curran had all that and his own look/s. He was a flash-fingered standout in a guitar town, a singer who could do Etta James and Bon Scott back to back. When he’d walk onstage wearing his trademark Brando motorcycle cap, tattooed arms hauling a big electric guitar, the whole place would get switched on, ready to rock.

And then he was gone.

His birthday was the anniversary of James Dean’s death, a date forever aligned with tragic unrealized potential. But even though gifted, hard-working and clear of vision, Curran was taken away before his Rebel Without a Cause moment. The skinny guitar player from Maine was still learning, evolving, mixing colors. Since he was a two-year-old playing drums during soundcheck with his father’s band, Curran was on a musical mission to put his own stamp on the nascent rock and soul echoes that possessed him. But cancer, that evil motherfucker, shot him down on Oct. 6, 2012 at age 35.

A few days later, the Black Keys dedicated their ACL Fest set to Curran, with guitarist Dan Auberbach wearing the t-shirt of the guitarist he’d wanted to record, but never got the chance.

At Wednesday’s Austin Music Awards on the Convention Center’s third floor ballroom, Nick Curran will be inducted into the Austin Music Hall of Fame. He will be acknowledged for his three years in the Fabulous Thunderbirds (’04- ’07), his five albums of wall-testing roots rock, his command of his guitar and his voice. But it will be a sad celebration. Many have not gotten over the loss, so the raucous joy in Curran’s music is shaded in sorrow. But be assured that, thanks to YouTube and music streaming services, future generations will hear that slicing, slashing, yelping guitar and feel the soul in those rock n’ roll vocals and know that Nick Curran was alive.

The one and only time I ever saw Curran play guitar, he came in late on a blues jam at Antone’s and took it to a special place. First there was his Freddie King-meets-Angus-Young guitar leads. But Curran also had a look- part East L.A. pachuco, part ’77 London punk- you don’t see in blues clubs. He was the most interesting thing all night without playing a note. I couldn’t wait to find out this guy’s story and write about it.

A few weeks or months later, I got a pink and black CD in the mail by Nick Curran and the Lowlifes called Reform School Girl. More than a bluesman, the guitarist/singer was a jump swing punk rockabilly metal guy with Little Richard in his soul. Working the record was the powerhouse Shore Fire Media of New York City, which signaled to me that this was the one Curran hoped would elevate him from cult hero status.

I called Shore Fire and set up an interview, but a few days later they emailed me a cancellation notice. Nick Curran had been diagnosed with oral cancer and would begin treatment immediately. This was about a week before the record came out.

Friends say Curran refused to let his illness beat his spirit and had “Fuck cancer” tattooed on his wrist. Curran’s last recording project was producing and playing on an album by the Sniffs, featuring his longtime friends Rafa Ibarra and Mike Parent. “Nick was always so positive,” says Ibarra, who rents the house Curran bought with his Fabulous T-Birds money from Nick’s mother. “He was going to beat this thing, there was no two ways about it.”

When Ibarra and Parent would drive Nick to Houston’s M.D. Anderson for his chemo, they’d come in a day early and get a motel room. Nick had a favorite place that he always went to the day before his 8-hour-treatment. It was a pawn shop in the Fifth Ward that was also a men’s clothing store. Pimp clothes. Stacy Adams shoes, orange pants, purple mesh shirts, jackets with zebra trim.

He’d recline in that chemo chair and think about the guitar he just bought, playing it in front of a cheering crowd. He looked perfect. And at the end of the night, the crowd knew they’d seen a special show. One they’ll never forget.

When the Continental Club had a tribute fundraiser in August 2012, a frail, weak, Curran insisted on riding his Harley to the show. He jammed with his friend Jimmie Vaughan, but it took his last bit of strength. Ibarra drove him home. “Nick rested up three or four days,” Ibarra recalls. “He saved himself for that night.”

When the Continental Club had a tribute fundraiser in August 2012, a frail, weak, Curran insisted on riding his Harley to the show. He jammed with his friend Jimmie Vaughan, but it took his last bit of strength. Ibarra drove him home. “Nick rested up three or four days,” Ibarra recalls. “He saved himself for that night.”

Son of an electric bluesman

Nick’s father Mike Curran was the best blues guitarist in Sanford, Maine. His band the Upsetters often featured a horn section so the band could do Bobby “Blue” Bland and jump blues right. His parents divorced when Nick was young and he lived mainly with his mom, but his father gave him his earliest musical education.

By his teenaged years, Curran had discovered rockabilly and quickly became a hotshot in the area. “Even when he was playing in greaser bands, Nick played his own way,” says Dave Wakefield, who played sax in the Upsetters. “He always knew what he wanted.”

The way he got to Texas was that Sean Mencher of High Noon, who had recently moved from Austin to Portland, Maine, got a couple of phone calls asking him to go on tour. One was from Ronnie Dawson and the other from Kim Lenz, both from Dallas. Mencher was settling down so he declined, but he told them about this kid from Maine named Nick Curran, who put a little blues with his rockabilly guitar.

That made a 19-year-old Curran perfect for Dawson’s band. He was ready to sponge up whatever he could learn from “the Blonde Bomber” of the Big D Jamboree. “Nikki had a natural curiosity,” says Diane Scott of the Continental Club, who met Curran when he backed Dawson in 1997. “He wanted to know how everything worked. He was always asking ‘how did you do that?’ And then he’d work on it until he could do it, too.” Curran sewed his own clothes and cooked for himself. He knew enough about electronics to customize his guitars and amps. His shit had to be his own.

He moved to Dallas in ‘98 to play guitar in Lenz’s rockabilly band the Jaguars. Curran met Dallas native Ibarra at the various blues jams around Greenville Avenue. “Nick had a studio apartment in the back of a barber shop and he played records all day,” Ibarra says. “Not just blues or old rock and roll. He loved N.W.A. and Guns N’ Roses. And, of course, he loved the Clash.”

Curran blew minds in 2000 when he released his first solo record Fixin’ Your Head on Texas Jamboree Records. It was old music- jump blues, R&B, rockabilly- scorched with punk flames. Curran went from little brother on the scene to someone that everyone looked up to.

Nick Curran got a tear tattooed to commemorate his father, Mike Curran, who passed away in 2010.

Curran moved to Austin in 2001 and lived with Buck Johnson of the Horton Brothers. A few years later, he got a apartment with Ibarra on Bull Creek in the same building as a bunch of musicians: Gary Clark Jr., bassist Ronnie James, members of Chili Cold Blood. He had too many ideas for one band so he played in several: the Hustlers, the Flash Boys, Deguello. He played drums, too.

Curran’s raw, unfiltered music appealed to a full spectrum of fans, including Joe Emery of the terrific garage band the Ugly Beats. Emery first saw Curran in the Hustlers, who played Sonics covers with a little AC/DC thrown in, then saw him in later incarnations. “As hard as his death hit me, and there were a lot of people who knew him way better than me,” says Emery, “it’s just impossible not to smile when listening to his music and think about how lucky we were to have him here for the time we did.”

Creatively, Curran went out on a high note with Reform School Girl which welded everything he loved- blues, glam, swing, girl groups, punk, etc. I doubt if that will end up being his final LP, however, as there’s quite a bit of great unreleased tracks.

Emery had written a song called “Up On the Sun” about two months before Curran died, but in the days following the stunner, Emery started thinking that the lyrics “No time for rearview mirrors” and “I’ve got to use the precious few hours left in the day” had special meaning. The Ugly Beats dedicate the song to Curran whenever they play it live and in the credits of upcoming album Brand New Day.

No time, no time, no time for what could be, what’s done is done

Come what may, if I have my way, you’ll find me out on top of the sun

The ones who die early make that sacrifice for the rest of us, whether they know it or not. They’re that one in a thousand that could’ve been us. It’s not fair, we know, but there’s a lesson in the loss. You’ve got a life. Now what are you gonna do about it?