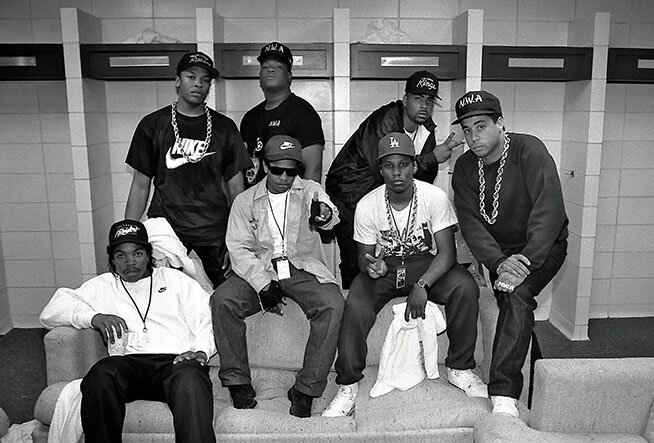

N.W.A. (back) Dr. Dre, Laylaw from Above The Law, The D.O.C. (front) Ice Cube, Eazy-E., MC Ren and DJ Yella (Photo By Raymond Boyd/Michael Ochs Archives/Getty Images)

January 1996 DALLAS.

His mother begged him not to sue. Rapper Tracy “The D.O.C.” Curry says this in a rasp that sounds a little like resurrection’s whisper and a lot like Miles Davis’ parched bark. “She’s afraid something bad is going to happen to me,” the 27-year-old Dallas native says from his new hometown of Atlanta. Once a chief lyricist for N.W.A., as well as a hit artist on his own, Curry claims he was also a founding partner in Death Row Records, the $100-million home paid for by Snoop Doggy Dogg, Dr. Dre, Tha Dogg Pound, and run by a CEO The New York Times recently called “the godfather of gangsta rap.” Now Curry, the forgotten soldier, is taking on this music business posse that’s beginning to look more like an army every day.

“I ain’t sayin’ I’m not a little scared,” he says, but “it’s time to get what’s mine.”

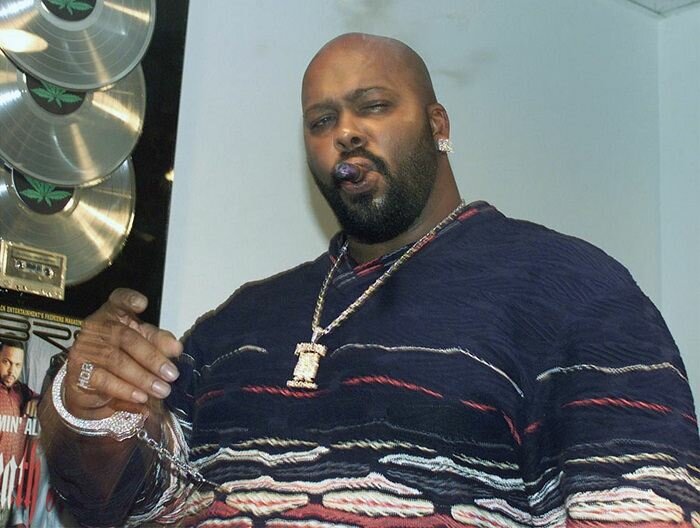

As usual, though, Curry will have to go through his ex-manager and former best friend, Marion “Suge” Knight, to get his money. The 320-pound Death Row Records chairman is not a soft touch. A former football star at the University of Nevada at Las Vegas who left behind the pads but not the spectre of violence, Suge Knight has a reputation for intimidation and an uncanny knack for getting competitors, like the late Eric “Eazy-E” Wright, to sign over assets for absolutely nothing in return except, perhaps, the opportunity to see another sunrise.

But Curry and L.A. Records chairman Dick Griffey have decided to take on the big man and his cash cow Andre Young (better known as Dr. Dre) anyway. Curry and Griffey are suing the label and its distributor, Interscope Records, for more than $75 million in general damages and $50 million in punitive damages. According to a 21-page lawsuit filed January 8, 1996 in Los Angeles Superior Court, Curry and Griffey entered into a partnership agreement with Knight and Young in January ’91 to form a music-publishing and record company that was first called Future Shock Entertainment and later renamed Death Row.

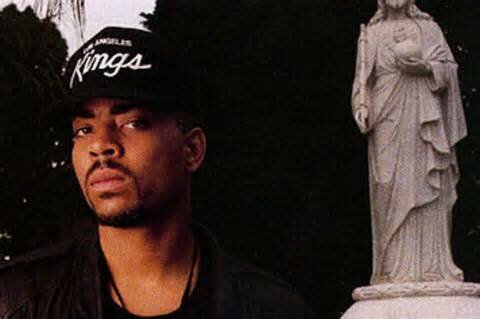

The D.O.C. on the cover of No One Can Do It Better 1989.

“I’m the one who told Dre to change the name to Death Row,” Curry says. “Dre was on Curtis Mayfield’s dick at the time, but I told him that name was corny as a muthafucka. [Mayfield had a hit in ’73 with ‘Future Shock.’] At the time, D.J. Unknown was trying to start a label called ‘Def Row’ and I told Dre, ‘Fuck that nigga, let’s call our shit Death Row,'” recalls Curry. (Curry is also credited by none other than Dre for “talking me into doing this album,” in the liner notes to The Chronic, Death Row’s first release.)

After Griffey procured a million-dollar publishing advance from Sony Tunes Inc./Sony Songs Inc. in 1991, the new corporation that became Death Row bought recording equipment, blocked out studio time, acquired the rights for Def Row from Andre “D.J. Unknown” Manuel, and started signing artists–including Cordozar Broadus Jr., better known as Calvin Broadus and completely known as Snoop Doggy Dogg.

You can’t tell it from his scratchy bray on the new sinister Helter Skelter LP on Giant Records, but the D.O.C. himself was once the most elastic and free-flowing rapper on the West Coast, with his 1989 debut LP, No One Can Do It Better, going double platinum. But just months after the record “blew up,” so did Curry’s follow-up dreams, as he fell asleep, drunk, behind the wheel of his car and drove off the road and into a coma.

The first concern was that Curry might not live, but after 22 hours of surgery, much of it reconstructive, he pulled through. The lasting injury, however, was damaged vocal chords that left him unable to speak for several months. “The only thing wrong with my voice is the way it sounds,” Curry says almost six years later, “and that’s getting better all the time.”

No longer smooth enough to rhyme “lyrical” with “superior,” Curry had to change his style to fit his excoriating voice. “I crossed over to the dark side, man, and I’ve seen what’s coming up at the end of the millennium,” Curry says. “The gangsta shit is gettin’ old. You can’t just get out there with a fine bitch and a blunt and a 40 [oz.] and work the crowd. That shit’s been played out.”

On the apocalyptic Helter Skelter (not-so-ironically, the working title for the proposed Dr. Dre-Ice Cube collaboration), Curry raps about rebirth, secret master-plans, the here-after, in addition to the usual odes to “Bitchez” and his “Doggs.” There’s also a rhyming legal brief, titled “From Ruthless to Death Row (Do We All Part),” which summarizes Curry’s past nine years: “I rose up quick from the pit/I was in 454 300 Benz/Nothin’ but ends/But friends got me in a cross/Now everything’s lost.”

“I don’t like to toot my own horn, but ‘toot-toot,'” Curry says. “I’m a lyricist f’real. My job at Death Row was to make sure that all the words that came out on the albums were the shit. I’m one of the only people I know who’s meticulous enough to go over every line, every word, to make sure it’s all there.”

Before the Dre-produced No One Can Do It Better hit on Eazy-E’s Ruthless label, the D.O.C. made his name in his new home of Compton as a writer, with early credits including tracks on N.W.A.’s instant blacktop classic, Straight Outta Compton (’88), and Eazy-E’s Eazy-Duz-It (’88).

“I was Eazy’s pen, because he couldn’t write lyrics,” Curry says. “The nigga couldn’t rap, either. Man, he had the worst rhythm.”

Better with numbers than words, Eazy-E turned Ruthless Records–a company he claims to have started with profits from drug dealing–into the hottest label in rap. The strain of violent, sexist “gangsta rap” established the previously ignored South Central scene as the vortex of new harder-edged hip-hop and infiltrated suburbia with tales of drive-by shootings and hooker mutilations.

At the same time, Curry insists, Eazy conducted business as if he were still on the street corner, with a focus on incoming funds and a disregard for paying out what was owed.

“In the hip-hop world, Eazy-E was the personification of evil,” Curry says. “He paid my hospital bill, about $60,000, but he made me pay him back, which is cool, except that I later found out that he paid the bill out of my share of a publishing deal he made for me. The muthafucka used my money and then made me pay him back.”

Curry also tells about the time he traded his publishing rights to Straight Outta Compton, which has sold more than five million copies and counting, for a gold necklace. “I was 19 years old,” Curry says. “I didn’t know about publishing back then, and I didn’t care. I was part of the hottest team in the rap game, and I just wanted to keep makin’ dope records.”

It was Suge Knight–whose Knightlife publishing company hit it big by owning seven tracks on Vanilla Ice’s To the Extreme blockbuster–who convinced the D.O.C. and Dr. Dre they were being ripped off by Ruthless. When Knight exacted their release from the label–allegedly giving Eazy-E a choice between a pen in hand or a lead pipe upside the head, according to Eazy-E in Jory Farr’s music-biz insider book Moguls and Madmen–Eazy-E and Ruthless filed a $250 million federal racketeering and extortion lawsuit against Dr. Dre, Curry, Knight, and Griffey. The suit was eventually dismissed, but Knight’s reputation as “the wrong nigga to fuck with” was solidified.

“The four of us had a plan and we set it into motion,” Curry says about the seeds of the partnership. “We used the money from Sony to build that company, and we did everything the right way, only I didn’t get no money, but now I goin’ get it.” He says the last part with a singsong swagger that sounds like one of his old raps.

“I’ve known Suge Knight a long time. Hell, I was even tighter with him than Dre was for a while,” Curry insists, “and to be totally honest with you, the dude ain’t all he’s cracked up to be.”

Now, if Curry can only convince his mother of that.

Dr. Dre met Curry in Dallas in 1987, when Curry was a member of the Fila Fresh Crew and Dre was in town as guest DJ on a weekly rap show hosted by Dr. Rock on KKDA-FM (K104). “Rap was just being born in Dallas, but I’d been rappin’ since I was 13, and I was already real good at the shit,” Curry says. “Dre heard me rap and, he says, ‘If you come to California, nigga, we can make some money.’ Me and Dre just clicked.”

Curry had no qualms whatsoever about leaving a Dallas rap scene that was full of copycats. “When they first came out, Nemesis [Fila Fresh Crew’s crosstown rivals] sounded like they were from Brooklyn or Queens, but then I came back two years later and they sounded like they were from Compton,” Curry says. “I’m a leader, not a follower, so I moved from the projects of West Dallas to the projects of Compton.”

Once in L.A., where he slept on Dre’s couch for the first year, Curry says he was reborn. “In Dallas, I was pretty good, but when I hit Cali I was suddenly the best. I don’t know what happened, but I was un-fucking-touchable.” Indeed, with No One Can Do It Better, the D.O.C. established himself as a raging new talent on the West Coast rap scene. Dr. Dre, who cooked up an awesome stew of live instrumentation and silky soul samples, left no question about who was rap’s best producer.

“Dre is the Quincy Jones of my generation, the complete master of the studio,” Curry says. “Every little sound you hear on his records, the nigga done complexed on for hours. He runs shit through his head a million times before he puts it down.”

Asked if he’s sad that his association with his mentor has apparently ended, Curry says, “It ain’t ever over. You just go through phases of your life when you do fucked-up shit, but the real problem ain’t Dre. In fact, Dre’s the one who’s been telling me that I needed to get a lawyer and go after my money.”

“This shit ain’t hidden,” Curry says of his claim that he was shafted by Death Row. “Everything I’ve been telling you is known by those muthafuckas, but they ain’t gonna say nothing because it ain’t their play. This is Suge’s shit, and what he says, goes.”

According to the lawsuit, Interscope heads Jimmy Iovine and Ted Field, who could not be reached for comment, met privately with Knight and Dre and induced them to breach their partnership with Griffey and Curry, with Iovine calling Griffey “a crook.” Dr. Dre was really the franchise, and Knight was his manager: Interscope saw no need to deal with anyone else.

Marion “Suge” Knight

“They just wrote me out,” Curry says. “[Suge and Dre] have a gangsta mentality, and that’s not really my mindset. Plus, I was there by myself. I didn’t have no gang with me. I was lost. I didn’t have no voice. I didn’t know what to do, so I just rolled with the punches until I could figure out what to do.”

Curry stuck it out with Death Row, overseeing and writing some lyrics for Dr. Dre’s massively selling The Chronic LP, as well as Snoop Doggy Dogg’s multiplatinum debut Doggystyle. “They were fuckin’ with me, but I got a love for my work, and I wasn’t ready to give it up,” Curry says.

Whenever Curry needed money, he insists, he had to go to Knight, and “Suge wouldn’t give me shit.” When Curry complained and talked about getting a lawyer, he was threatened with bodily harm, according to the suit.

Suge Knight could not be reached for comment, nor could Death Row’s attorney David Kenner, who’s busy defending Snoop Doggy Dogg at his trial for his alleged part in the 1993 shooting death of Philip Woldemariam.

“They intimidated the D.O.C. right out of Los Angeles,” says Joseph Porter, Curry’s attorney. “He was afraid for his life. I’ve been threatened, too. Someone from Death Row told me that bad things happen to people who go up against them, but where does it all stop? When you do evil for a long period of time, it catches up to you, and I think we have an incredible case with stacks of documentation.”

Curry says he’s all the way back, and the accident that took his rapping skills and almost his life was a message from God.

The D.O.C. circa 2004.

“When I was in that hospital bed,” he recalls, “I’d think back when I was a little kid in Dallas, and I’d pray to God: ‘Please let me be the best. If you do that, I’ll do right and let everybody know that it was you that put me there.’ But after I got there, I reneged on my part of the deal. I was arrogant, and I thought I was invincible.”

The night of the ghastly car accident, Curry says he was stopped by police in Beverly Hills and charged with a DUI. Instead of being arrested and taken to jail to sober up, however, Curry was simply given a ticket and sent on his way. Before driving off, however, he joked with the cops and took pictures of them holding his platinum record. Three hours later, Curry went through the windshield of his car and into what he calls “the edge of darkness.”

“Can you believe those cops letting me go?” he says in that fucked-up voice. “Hey, maybe I should sue them.” Then Curry lets out a gruff guffaw. Irony is not lost on this rapper who was deserted first by his voice, and then by his friends.