Before I get into his high-profile return to the global concert course after a decade-plus hiatus, I should thank Garth Brooks for helping me get my first full-time writing job, with the Dallas Morning News. That was 22 years ago when our Mr. Brooks was the biggest thing in the entire music biz, not just country. His first three albums- Garth Brooks, No Fences, and Ropin’ the Wind– sold almost 20 million copies in the U.S. in three years and his spectacular live shows brought rock fans over the fence. The Dallas-Fort Worth distribution region was the #1 market for country music, accounting for a whopping 26% of Nashville label CD sales in 1991, so the Morning News created a full-time job to cover Garth and the emerging twang gang.

I was living in Chicago, not just freezing, but freelancing my ass off, so I had quite a few good clips on prestige artists Rosanne Cash, Dwight Yoakam, Lyle Lovett, k.d. lang, Townes Van Zandt and others, plus some appreciations of living legends like George Jones and Merle Haggard. I got the DMN job, starting in January 1992. Thankfully the Judds, who I thought were sisters, did not come up in the interview. The truth was that I didn’t know much of anything about mainstream country of the present, and the Internet came too late to make me an expert.

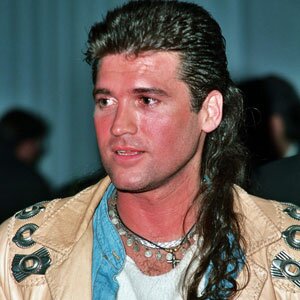

Nashville country, at the time, had more eye-bugging than a Don Knotts film festival, as every act was trying to look as downhome and “Hee Haw” as possible amid the authenticity police. But “Are you a real cowboy?” became moot when along came Billy Ray Cyrus, looking like Mel Gibson with a ferret running up the back of his neck, and folk/pop singers such as Mary-Chapin Carpenter (who I pegged “Mary-Blatant Carpetbagger”) and the faux duo Brooks & Dunn (“Loggins and Oates”) crashing the lucrative marketplace. There were also all these soft-rock acts like Diamond Rio, who looked like the men’s room line at a Toto concert. For someone whose life was changed by Patti Smith’s Horses in 1975, early ‘90s country music was like stumbling from a Bukowski dive bar into Dave and Buster’s.

Nashville country, at the time, had more eye-bugging than a Don Knotts film festival, as every act was trying to look as downhome and “Hee Haw” as possible amid the authenticity police. But “Are you a real cowboy?” became moot when along came Billy Ray Cyrus, looking like Mel Gibson with a ferret running up the back of his neck, and folk/pop singers such as Mary-Chapin Carpenter (who I pegged “Mary-Blatant Carpetbagger”) and the faux duo Brooks & Dunn (“Loggins and Oates”) crashing the lucrative marketplace. There were also all these soft-rock acts like Diamond Rio, who looked like the men’s room line at a Toto concert. For someone whose life was changed by Patti Smith’s Horses in 1975, early ‘90s country music was like stumbling from a Bukowski dive bar into Dave and Buster’s.

I just didn’t know what to make of my new beat, but there was one thing of which I was certain: all I had to do to keep my job was become the world’s biggest Garth Brooks expert. He was such a phenomenon, creating a New Nashville where it was okay to admit that you grew up on Kiss, that you couldn’t lose if you hitched your career to his rocket rise. Dallas was Garth’s city, close to his home state of Oklahoma, yet far enough away to serve as a proving ground. It was there at the State Fair of Texas on the night of the 1990 Texas-Oklahoma football game, that “Garthmania” came into this world. Tens of thousands of Brooks fans, some climbing trees to see, wouldn’t let the Texas-loving Okie leave the stage until he sang every damn song the band knew.

Whatever Garth did, I was there. For three years. Every press conference, every concert within a 100-mile radius. If he belched I could tell you what he had for lunch, but Garth never belched. He was perfect.

And he always kept his word. Thirteen years ago, Brooks announced that he would take a break from the music business glare to raise his three daughters. He moved back to Oklahoma with his second wife Trisha Yearwood and gave his kids as normal an upbringing as possible when their daddy was selling more records than the Beatles. After his youngest daughter graduated high school in May, Garth Brooks was free to take his empty nestmobile all over the world.

Garth’s Act II was supposed to begin July 25, 2014 in Ireland, where the melodramatic man in the cowboy hat is more folk hero than country singer. Brooks quickly sold out five shows at 80,000-capacity Croke Park in Dublin, but citing noise and unbearable inconvenience, residents revolted and threatened to sue the promoters. The Dublin City Council offered a compromise of three Brooks concerts, but Garth said he’d play all five or none. He didn’t want to uninvite 160,000 ticketholders, so the shows were cancelled, which made the U.S. tour kickoff Sept. 4 in Chicago. Garth and the marketing team in his head treat each concert stop like a new product rollout, annoucing one city at a time and then playing as many shows there as the demand dictates. Garth’s return to Dallas, at the American Airlines Center, will be Sept. 18 & 19 (and 20, 21, 22, 23, 25…), with tickets going on sale today (July 24).

I think Brooks has released a studio album with new tunes, but it’s always about the live show. Garth put out a bunch of good songs in his heyday, with “Friends In Low Places” his signature tune, but his greatest innovation was bringing the full-on rock and roll experience to country music, while keeping his personal connection with fans.

I think Brooks has released a studio album with new tunes, but it’s always about the live show. Garth put out a bunch of good songs in his heyday, with “Friends In Low Places” his signature tune, but his greatest innovation was bringing the full-on rock and roll experience to country music, while keeping his personal connection with fans.

“Once you’ve seen him live, all his success makes sense,” Garth’s label boss Jimmy Bowen told me in 1992 for a feature that basically asked, “Why Garth?” Wearing one gaudy, colorful rodeo shirt after the next, Brooks smashed guitars, set off explosions and sashayed around elaborate sets, singing from a mic built into his Stetson. “Who says country singers have to just stand there?”

A man of the people

In 1989, the year Garth broke out with tear-jerker ballad “If Tomorrow Never Comes,” the king of country was Clint Black, who, like Brooks, started out singing pop/folk numbers like “Please Come To Boston” at pizza parlors. Both put on the magical cowboy hat, which instantly transformed them into country singers, but Black, who shared management with ZZ Top, didn’t know how to work the good ol’ boy network like Garth did. Garth stayed humble, once signing autographs for 23 hours straight without a break. He kept ticket prices at about $18 and fought scalpers for the good of his true fans. And he was generous, often donating his concert fees to local charities. When Garth played The Tonight Show with Jay Leno, he sang from the steps in the audience, just him and a guitar. He never missed a trick.

His music wasn’t quite on a quality level of Dwight Yoakam or Patty Loveless, but Garth sold his songs by being fully committed to what he was singing. I dubbed him “Ol’ Dew Eyes” because he would often be overcome with emotion in concert and the spotlight would show a single tear streak down his face. Stepping into a “Garthfield” love-fest was like being taken aboard an alien spaceship sponsored by Hallmark. The fans would bring gifts- cards, flowers, stuffed animals- to the edge of the stage and Garth would pick up every single one and hold them to his chest. It was a little hard not to join the cult.

Billy Ray Cyruc, 1992, and the hairstyle that defined the changing genre.

Brooks had “crossover” potential like no one since Dolly and Kenny sang “Islands In the Stream” and yet his bombastic 1992 cover of Billy Joel’s “Shameless,” which shot to #1 on the country charts, was not marketed to pop radio. Capitol’s Bowen: “We don’t care if pop radio plays Garth. We want the radio audience to come over to country stations and hear our other artists.” It was a good strategy, as the white flight to country radio made it the #1 rated music format for the first time in 1991. Garth was high tide, raising the ships of MCA acts like Reba McEntire and Vince Gill, Arista’s Alan Jackson, Mercury’s Shania Twain and Curb’s Tim McGraw.

Tim DuBois, who built Arista Nashville into a powerhouse label in less than two years, had high hopes for the New Nashville when I interviewed him in 1993. “My job is to put out good albums, not to try to cash in on the latest thing,” he said. But there was a new sensation in country music nightclubs that couldn’t be ignored: “house country.” Arista released dance remixes of such songs as “Boot Scootin’ Boogie” by Brooks & Dunn, “Chattahoochee” by Alan Jackson and “Cleopatra, Queen of Denial” by Pam Tillis to the growing number of country clubs where you were as likely to hear Madonna as Wynonna, Michael Jackson as Alan Jackson and MC Hammer as M-C Carpenter. New Top 40-modeled country stations like KYNG (“Young Country”) in Dallas started playing the beat-enhanced versions, and just like that, Urban Cowboy II had its very own mechanical bull. Add in the hulking, hunking presence of country’s Chippendale dancer Cyrus and his “Achy Breaky Heart” and you had disco with a southern accent. Country line dancing is just “The Hustle” in a rodeo shirt.

“Very little is distinguishable,” Bowen said in ’92. “I think (the current product) is going to do serious damage to country music, but it looks like I’m the only one.”

With the flood of new audiences, many raised on James Taylor and rock n’ roll, in addition to disco, mainstream country music has become increasingly watered down. It’s not fair to blame an act for the crap they inspired, but just as you can trace any white funk/rock band with shirtless, long-haired singers to Red Hot Chili Peppers, today’s “bad rock n’ roll” phase of country music goes back to Garth. The main difference is that the mega-selling “thumb in a cowboy hat” didn’t have to thank his personal trainer when he won an award.

The shirt from Texas Stadium shows.

Spinal Hat

Garth Brook’s Achilles heel was hubris. Not many trends or fads have the luxury of knowing exactly when they peaked and started heading back toward normal, but for country music’s early ‘90s boom, the pivotal moment occurred on a hot September night in 1993 when Garth Brooks tried to take his hat act to the Stadium Age and got soaked in posture and pretense. His three concerts at 67,000-capacity Texas Stadium, which sold out in a couple hours, had been hyped as the most spectacular country music event in history. “You’d better bring an umbrella,” Garth teased about the effects for “The Thunder Rolls,” but instead of a storm over the audience, the water trickled down like a leaky faucet. There were so many malfunctions and uncomfortable moments that the suggested headline for my first-night review was “Spinal Hat.”

Because the shows were filmed for an NBC special, the sound was tamed for TV and there were no big screens for those in the rafters to see what was going on. Subsequently, I saw about three fistfights in the upper deck, giving new meaning to “nosebleed seats.” They couldn’t hear, they couldn’t sing, so they made their own entertainment.

The funny thing about heroes is that sometimes we want them to fail and I have to admit that I was beaming after Sir Garth soiled the Sealy on that first night at Texas Stadium. He brought the gleeful derision upon himself by being defiant to the working press. Photography at the concerts was absolutely forbidden, with Brooks saying that he wanted the TV audience to be seeing his new yellow and black shirt for the first time when they saw his special. Also, there would be no concert tickets for critics, who had to watch from the press box a thousand miles away. When that first concert started going south, the “no cheering in the pressbox” rule went out the window. Dealing with control freak Garth and his people all week was such a drain that the come-uppance was refreshing.

And the Dallas Morning News got its photos anyway. Some genius set up a photo essay of Jerry Jones on “country music’s biggest night” and the camera in the Dallas Cowboys owner’s luxury box caught the action onstage.

The next day the calls in to the three top country radio stations in town were brutal. Usually the listeners blasted my negative reviews of acts like Alabama, Reba McEntire, Sawyer Brown and Faith Hill, but the morning after the first Texas Stadium show, they echoed many of my complaints. You can be sure that Garth, who lived in a tour bus parked inside the stadium for a week before the shows, read the reviews and listened to the radio. It was the first hint of a backlash in his career.

Brooks just got too big too fast, and so he slowed down. Instead of delivering an album a year, he made it every two years, with Fresh Horses in ’95 and Sevens in ’97. Then a break of four years to Scarecrow, the contractual commitment LP, which released four singles, none of which topped #5 on the country charts.

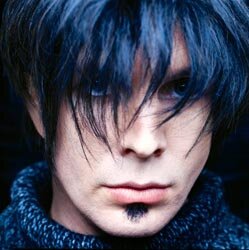

Garth as Chris Gaines

But the first phase of Garth’s career effectively ended with the release of Greatest Hits by Chris Gaines, an Australian rocker who looked a lot like Garth with a soul patch. Coming off less about alter and more about ego, the Chris Gaines fiasco was a message to step off the gas. The piling on was merciless. When Garth Brooks failed it was like a right-winger shown in naked photos with the pool boy.

Another misstep in ’99 was when Brooks named his children’s charity, Touch ’em All Foundation. The name, baseball slang for running the bases after a home run, came from Garth’s stint as a member of the San Diego Padres in Spring Training. But it showed the country superstar to be rather out of touch, pardon the pun.

But Garth Brooks was not going to bow out at such a low point. Months before the release of Scarecrow in 2001, a recently-divorced Brooks chose the occasion of his passing the 100 million mark in total album sales to announce that he was retiring to raise his daughters in Oklahoma. He would not make a record or tour, he vowed, until his youngest daughter graduated from high school, which happened in May 2014.

Although he performed one-off concerts here and there, usually for charity, and signed a five-year deal with Wynn Resorts in 2009 to play weekends in Las Vegas, Brooks has kept his word.

But early 2014 found Brooks navigating his return. On Feb. 6 he performed “The Dance,” his 1989 hit about taking risks, on the final episode of The Tonight Show With Jay Leno. It’s a corny song, but one that hits deeply with many. What better way to announce that Ol’ Dew Eyes is back?