by Michael Corcoran

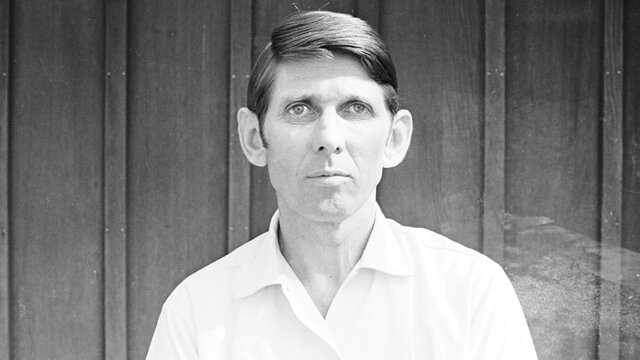

Burton Wilson

Burton Wilson’s camera was Austin’s memory during the hippie era when, as the saying went, if you could remember it, you weren’t there. The former Vermont farmboy who documented the vibrant scene at the Vulcan Gas Company in the 1960s and the Armadillo World Headquarters in the 1970s passed away Monday morning. He was 95.

Wilson got it down while those around him were only concerned with getting down. In the process, he created the defining documents of an enchanting era in Austin’s history.

“Burton was one of my mentors,” said photographer Todd V. Wolfson. “He made me want to chronicle MY Austin, as he had done.”

I had the pleasure of profiling a still-lucid Wilson, who occasionally snuck a joint when his wife Katherine was out, seven years ago. “I was a huge fan of the early years of New Orleans jazz, but there was almost no visual documentation of that era,” said Wilson, who was married for 66 years at the time. “I knew that if I ever discovered a magical music scene, it would be my calling to document it. The hippies were doing something that had never been done before and I was smart enough to realize that it was something special.”

You almost never see any pictures from the Armadillo not taken by Burton Wilson who, at age 51, approached the club’s honcho Eddie Wilson, then half his age, for permission to take photos at the new longhair haven in 1970. Burton promised two things: to stay out of the way and to provide copies of any photos.

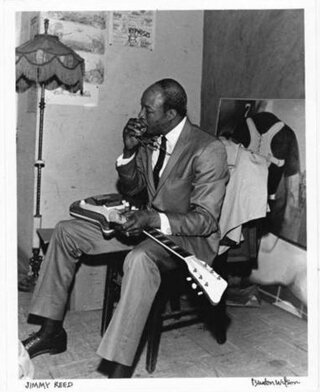

Big Joe Williams at the Victory Grill

A student of Depression-era photographer Russell Lee, who taught the first photography classes at the University of Texas in 1965, Wilson learned to be as unimposing as possible, to use only available light. His Nikon became one with his body, as the ever-handy Burton fashioned a mini-tripod that sat on his chest and hooked onto his belt.

The anti-paparazzo, Wilson displayed the utmost respect for his subjects and was rewarded with the relaxed, unguarded and generally warm backstage shots that became his specialty.

“I think a lot of the musicians liked me because I didn’t pose them,” Wilson said. “And I didn’t take a lot of shots like you see them do now. I had to buy my own film, so if I felt like I got a good shot, that was it.”

One such single click was enough to land Wilson the cover photo of Johnny Winter’s 1967 debut album “The Progressive Blues Experiment.” The local Sonobeat Records had hired Wilson to shoot a standing pose of Winter in front of a white background. “They were very definite about what they wanted,” Wilson said. “But when I had one last exposure, I wanted to try something else. Johnny picked up his National steel guitar and you could see the reflection of his face, so I snapped the photo.”

Sonobeat sold the recording and the artwork to Imperial Records, which chose Wilson’s arty shot for the front cover and used the posed photos on the back.

“Burton has this Old World charm and grace about him that made him cool without even trying,” said Eddie Wilson, no relation. “Compared to the rest of us testosterone-driven idiots, he was like from another planet.”

“Burton has this Old World charm and grace about him that made him cool without even trying,” said Eddie Wilson, no relation. “Compared to the rest of us testosterone-driven idiots, he was like from another planet.”

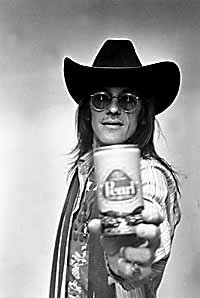

In the era of the generation gap, the nonjudgmental Burton Wilson fit in, whether it was in the audience of a Van Morrison show or hanging backstage with Doug Sahm, Leon Russell and the Grateful Dead as they were deciding to do a free Thanksgiving show at the Armadillo the next night.

The “never trust anyone over 30″ youth culture motto didn’t apply to the fifty-something in the square, horn-rimmed glasses. “One day an attractive young woman approached me and asked if I would take her picture,” Wilson recalls. “Then she said, ‘But I want to be naked.'” With Katherine’s approval, Wilson took the artsy nude photo. More young women who frequented the club asked Wilson to shoot unclothed photos of them; his collection of nudes eventually topped fifty.

Sometimes the musicians came to Wilson, but sometimes he had to go to them and wait patiently for the perfect shot. The photograph he called “my Mona Lisa” was taken at the end of a long day in East Austin with Mississippi blues singer Big Joe Williams, best known for “Baby Please Don’t Go” and his nine-string guitar. The beautifully stoic shot of the big proud man who’d been through troubled times, having a cigarette after supper at the Victory Grill, was a favorite of mentor Lee’s.

Wilson was in his mid-40s when he took up photography. A 1941 graduate of the Rhode Island School of Design, Wilson had a setback in his goal to become a world-class sculptor when an artillery blast in World War II nearly killed him, leaving him unconscious for 21 days.

Burton and Katherine Wilson moved from Dallas, her hometown, to Austin in the late ’40s. “Austin was just a small town back then, so we bought 15 acres in West Lake Hills, off Red Bud Trail, and built our house,” Wilson says. They sold the property in 1975, long before it was worth millions, and moved to California for seven years.

Wilson was living on his disability check and making and selling pottery with Katherine when he heard in 1965 that Lee would be teaching the first-ever photography class at the University of Texas. “It was just too good of an opportunity to pass up,” said Wilson, who became good friends with Lee. Like Wilson, Lee was a northerner who had married a Dallas woman, which brought him to Texas.

Wilson had heard about the Vulcan Gas Company club from his son Minor, a guitar player and repairman who was friends with Janis Joplin, the 13th Floor Elevators, the Grateful Dead and others. But it was the bookings of nascent blues players such as Lightnin’ Hopkins, Sleepy John Estes and Mississippi Fred McDowell that first drew Wilson to the Vulcan.

Ironically, it was the Wilsons’ record collection that turned the future bookers of the Vulcan and the Armadillo onto old country blues in the first place, according to Eddie Wilson. “Back before the Vulcan opened (in 1967) the cool thing to do after a concert, like when Dylan played (Austin) in ’65, was to go to Burton and Katherine’s and listen to records. They turned everyone on to so much great old blues music.”

Jimmy Reed

The folks at the University of Texas’ Barker Texas History Center (now called the Center for American History) had heard of Wilson’s record collection and asked if they could tape part of it for their archives. He agreed under the condition that he receive copies of the tapes. The center sent back 38 reel-to-reel tapes containing 836 rare songs.

Wilson keeps meticulous records of what’s on those tapes, just as he does with all his photographs.

His organization was so precise, he actually helped solve the 1975 killing of Armadillo bouncer and poster artist Ken Featherstone, who was shot to death by a patron who had been prevented from leaving with an open container and vowed revenge. Armadillo security chief Dub Rose recalled that, a couple years earlier, he had a scuffle with a man who fit the killer’s description and turned him in to police. Rose remembered that Wilson had taken a picture of him wearing a new cowboy hat the night of that fight. Wilson was able to produce the date of the photo, and the killer was identified through his police mug shot from the earlier incident.

The whole story, as written in the Austin Sun, is in a frame on the wall of Threadgill’s, along with all the memories that Burton Wilson’s camera has kept alive.

Threadgill’s was Wilson’s second home, first the original on North Lamar, where he used to make a fresh pot of coffee for himself every morning to 20 years, to the newer Threadgill’s, where he and assistant Jack Ortman spent most Fridays in recent years IDing photos on the walls. When I was working on the story seven years ago, Ortman pointed to a photograph of Fats Domino playing to an ecstatic crowd of longhairs in 1971. “If you look real close, over near the front of stage left you can see a guy holding up his 3-year-old kid to see Fats Domino,” Ortman said. “That’s Doyle Bramhall holding up little Doyle.” Eric Clapton’s guitarist Doyle Bramhall II has proof that he saw a New Orleans legend in concert at an age when most kids were stuck on Captain Kangaroo.

“Bill and Hillary Clinton used to live a couple blocks from the Armadillo in the early ’70s,” Ortman said, “so we’ve been scouring every single crowd shot, hoping to see them, but we’ve turned up empty so far.”

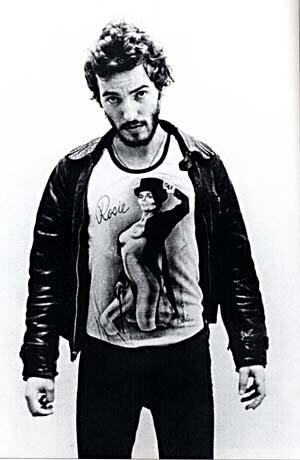

One of Burton’s most famous stories to go with a photo was about the shot of Bruce Springsteen, then 24, wearing an airbrushed shirt depicting a woman wearing only a top hat, coattails and a smile. “Rosie,” it says, perhaps in reference to Springsteen’s showstopper at the time, “Rosalita.” Or maybe one of the two women desperately trying to get backstage to give the shirt to the man not yet known as “the Boss” was named Rosie.

One of Burton’s most famous stories to go with a photo was about the shot of Bruce Springsteen, then 24, wearing an airbrushed shirt depicting a woman wearing only a top hat, coattails and a smile. “Rosie,” it says, perhaps in reference to Springsteen’s showstopper at the time, “Rosalita.” Or maybe one of the two women desperately trying to get backstage to give the shirt to the man not yet known as “the Boss” was named Rosie.

“I knew one of the women,” Burton Wilson recalled, “so I told the guard it was OK to let them back. They made Springsteen take off his shirt and put on the one they had made for him and I asked if I could take a picture.” Springsteen’s priceless expression is a mix of quizzical and defiant. He wore the “Rosie” shirt throughout the three-hour show, but had sweated away the airbrushed design and at the end of the night the T-shirt was blank.

Just as a huge chunk of Austin’s history would be if not for a charming gentleman who promised to stay out of the way.